So for Discussion 1 you had two stories to think about. Let's onsider the very short story called "All About Suicide," by Luisa Valenzuela.

who kills whom?

That seems like it should be simple enough. The story is short, and that's just a plot fact you are looking for.I open my face-to-face classes with this question, and typical answer look like this:

- Ismael kills the minister (by the way, this is a political postion, like Secretary of Defense in the U.S.)

- Ismael kills himself (after all, the title is "All About Suicide")

- Ismael kills the minister then he kills himself

- Ismael kills the minister and then thinks about killing himself

- Ismael forces the minister to kill himself

- Nobody kills anyone; Ismael is planning to kill the minister and trying to work up the nerve

How can there be so many answers? This is so short that it should be obvious. What is causing the ambiguity? The answer to that is there are lots of tricky bits to look at in Valenzuela's story, and they are not there accidentally.

but wait! why are we doing this again? it's not like any of this is real!

Last week we puzzled over how humans pass along their story, their history, a sense of who they are so that their civilization(s) can be known by others that follow. We also noted just how hard that is since what gets passed along (over very long periods of time) is quite fragmentary. What would tell us more about a culture--a shopping list or box score from a newspaper or stock market readout or a weird short story like "All About Suicide"? Consider this:

You find a ledger from what was presumably a farm 5,000 years ago. You manage to decipher the language, and you discover that they presumably had 5 bushels of wheat one harvest.

Very cool, that is a SOLID FACT, HARD INFORMATION. But what does it mean?

Nothing. Out of context, that number and that crop mean nothing. Is that a lot? Was it a horrible year for them? There is nothing to relate it to. It's an isolated fact that reveals very little about culture.

Stories, poems, plays, music, art, architecture, mathematics, and so on--these are all forms of communication, and fiction (like Valenzuela's story) reveal theme. On our class home page, I mentioned that in literary analysis, the word theme has a very special meaning. A theme is a complete idea (not a single word); it is generally expressed in a sentence. It explores some subject (such as LOVE) and makes a conclusion about that subject, and it shows how a writer feels about a topic or has summed up a life's experience or expresses a set of beliefs and values. Here are some very different themes about LOVE:

- Love is blind.

- Love conquers all.

- All you need is love.

- Love makes fools of us all.

- Love stinks.

- etc.

Each one of those is a short, complete sentence/thought. The ideas do not all agree with one another (as there are many ways to look at love), but did you notice that all of those are cliches (cliche is another literary term)? Cliches are so over-used they have lost their impact; they feel like throwaway lines or thoughts. They become that way because the idea is written by writers over and over through the ages. That does not mean they are nonsense; it means they are common; it is how humans have experienced life consistently through the ages and across the globe. It is an essential human truth and is at the core of what a group of people believe, value, experience.

It is a lot more telling than "5 bushels of wheat."

And so, ultimately, we want to try to figure out why the author is making us puzzle over this and what it might all mean, because that will share something about this author's view of life, the universe, and everything.

But it really is a puzzle, like unraveling a mystery. We are looking at some examples of action, characters, places, things that express an idea to someone else from somewhere else, and we have to try to get into the head of that other (possibly long-dead) writer and figure out what the story suggests.

We do this by looking for unusual patterns (like the car engine that is going ker-THUMP ker-THUMP). We must look closely at all of the parts that might cause this confusion.

dissecting/diagnosing the story (in the process, you will see what looks a lot like an analytical essay :)

The title suggests that Ismael kills himself; that is what suicide means. However, there are many kinds of suicide (political suicide, business suicide), so that might be ambiguous. The first few sentences, though, describe a physical suicide: "Ismael grabbed the gun and slowly rubbed it across his face. Then he pulled the trigger and there was a shot. Bang. One more dead in the city. It's getting to be a vice" (Valenzuela). This is, in essence, the whole short story. It has a beginning; the action rises to a critical point; there is a climax (where Ismael pulls the trigger), and the short resolution is that he is dead. There is also the suggestion of a place (setting) where death is so common it is just considered "a vice," like smoking or drinking. A little research shows that the author is from Argentina, and her writing is rooted in the religoius and political unrest that has characterized certain periods in Central and South America. So far, the only name we have is Ismael, and when we look for a name to connect to "his" and "he" (this is called pronoun reference), all we have is Ismael killing himself.

Then the author decides to tell the story over. This seems redundant, but, really, a short story that is only a few lines long is not very satisfying. Readers like more detail, more dirt. The re-telling is not much longer, though: "First he grabbed the revolver that was in a desk drawer, rubbed it gentrly across his face, put it to his temple, and pulled the trigger. Without saying a word. Bang. Dead." There are some descriptive details now--where the gun (a revolver) was taken from, how it was rubbed across his face (gently), and where it was placed (the temple). Authors add detail to give the reader a clearer picture, to make the story feel more real. But, really, not much has been added, and we still have only Ismael named, so Ismael killed Ismael. It is not just planning a death, either; we have in both versions, so far, "Bang" and "dead."

The author decides to "recapitulate" (give the reader a re-cap, to go over it again). Certainly, a magazine is not likely to print a one-paragraph story, so she has to give the reader more. Paragraph two adds more details--the grand office, the sensuality of rubbing the gun across the face. We do have the word minister, but it only refers to an office, not a person, so all of the he, him, his pronouns still refer to Ismael. There are now three short versions of the story that all suggest Ismael killed himself.

Feeling that this does not really tell the whole story--"There's something missing"--Valenzuela sends the reader to a bar where Ismael is mulling over the consequences of his future actions, then further back to Ismael in the cradle being ignored, a bit further forward to Ismael in elementary school making friends with someone who will become "a minister...a traitor" and then to the decision that something unnamed is so horibble that it is better to accept death, but whose death? This longer section gives the reader much to think about. Was Ismael somehow warped because he was ignored as a baby? That sounds like the sort of psychological motive that might show up in a court case. If Ismael befriends someone who will later have political power and betray his authority/country, why wouldn't Ismael just go to the newspapers? The government likely controls the media, so if the government is corrupt, that will remain secret, and, likely, Ismael will be silenced with death, so it seems he feels it is his obligation to fix the problem by killing the minister. At this point, all of the he, his, him references in the story can be re-evaluated. Is Ismael rubbing the gun across "his" (the minister's) head?

There is now some background, and there are possible motives (psychological, political) for killing a traitor, but Valenzuela adds to the confusion.

Describing baby Ismael crying with his dirty diapers, the author follows with "Not that far." In other words, this is not something that the reader should consider.

It gets worse. Describing the most solid motive, the friend who becomes a traitor, Valenzuela follows with one word--"No." In other words, that would make sense, but it is off the table; it is not an explanation.

Going back, there are more (not fewer) problems. Is Ismael really rubbing the gun across the minister's temple? Did the minister say, "Oooo, Ismael, that feels so good. Could you rub my neck while you're at it?" Is Ismael slowly rubbing his own forehead? If so, why isn't the minister reacting? Then there is the final paragraph which suggests Ismael shoots the minister and then himself ("another act immediately following the previous one. Bang"). If he also shoots himself, how does he come out of the office "even though he can predict what awaits him"? Yes, this country would be predominantly Roman Catholic, and the consequence of suicide would be eternal damnation, so this could be a supernatural ending.

The problem is that it could be lots of things. That's ambiguity.

The retelling of the plot with additions and changes each time suggests that the story might have a different point altogether. If Ismael killed the minister or himself or both, and if the reader is trying to figure out what happened and why, that puts the reader in the position of a survivor looking at someone who was so desparate they actually killed. If it were a friend or family member the questions, "Why?" and "What could I have done?" would be examined and re-examined with different details and from different angles. In the end, the survivor would never really have an answer. In the end, perhaps, that is "All [that can be known] About Suicide."

ok, so what is the correct answer?

Now this is both the beauty and the madness that is literary analysis (really, all kinds of analysis). If it is a truly thought-provoking work, there probably are several ways to logically look at it. Your job is to back up your claims/conclusions with evidence (details from the literature). As long as your evidence is consistent and fairly represents what is in the story, it is a reasonable claim/conclusion. There are probably several reasonable ways to look at various works of literature. As long as you can back it up fully, logically, with evidence, then it is "right" (though likely not the only "right" way to look at the literature). This is an exercise in logic and evidence (and sometimes even research).

Oh, and just to blow your mind a little bit more, you might want to consider this:

The theme of Akutagawa's "In a Grove" may be very close to the same theme as Valenzuela's "All About Suicide."

Enjoy :)

wait! what? what does this teach us?

Quite possibly we learn lots of things, but the two ideas that I hope stand out most are:

- the stories (poems, plays, novels) that get shoved in these literature anthologies are not always simple; they contain ambiguity; they require reading, re-reading, note-taking, thinking.

- to try to make sense (get to the meaning or theme) of these stories, you need to read really, really closely, just as I went through "All About Suicide" almost sentence by sentence.

If you casually breeze through the stories, of course you are likely to throw up your hands and say, "I don't get it." If we go back to that car analogy from Lecture 1, it would be like going out to your car, turning the key, hearing the ker-THUMP, throwing up your hands, and saying, "Something's going on, but i don't know what it is" and then just driving away ignoring the (ominous) noise.

Analysis takes some time, but the good news is that there are certain elements you can look for to make the process easier. Your textbook breaks down several literary elements that may be significant in the story you are reading. For example, "How to Talk to Your Mother (Notes)" (one of this week's discussion options), would not work if Ginny were born in 1995; time and place are important in that story, but sometimes setting is just setting and not particularly significant. We will be looking at some literary elements in an upcoming lecture, and that might help you, but here is a method that works pretty well and works quite often, and it's simpler than having to learn symbolism and figurative language and all that.

look for patterns and peculiarities

But let's come back to this in a bit; let's go backwards (this lecture is going to go backwards for a bit)

the steps: starting with the first (quick) reading and ending with an essay

Your text explores how to read through, take initial notes while reading actively, and so on. If the goal is to discuss or write about the story, then you will need to figure out what it means (and, remember, it can mean more than one thing). That conclusion can usually be framed in a thesis statement:

The repetitious plot structure of Luisa Valenzuela's 'All About Suicide' suggests that no matter how many times someone tries to make sense of suicide, it cannot really be fully known."

But wait, that was not immediately apparent on the first quick reading. That took a whole lot of analysis to arrive at. True. The thesis is rarely created after the first quick reading. It comes later. Before that, you need to ask questions about what you read. If we can eventually answer those questions, the answers will become the thesis statement(s) that will launch your discussion or essay. We are going to try this out with John Updike's "A&P" (be sure you have read the story, or this will not make much sense).

So I read the story, "Blah, blah, blah." Stuff happens to people I don't know. Sammy is the narrator, and at the climax (the point where the story makes its ultimate turn; typically, the main character makes a choice or fails to) of the story he quits his job at the supermarket because he feels his boss is embarrassing these three girls in bathing suits. After that he goes out to the parking lot hoping to see the girls, but they are gone (those things that happen after the climax are called the resolution).

Not much happens. All things considered, I would rather watch an episode of Twin Peaks or Sense8. Still, the story is in the textbook, and it was assigned, so I better look for something here. I have a few immediate questions:

- Is Sammy just a dumb kid who quits his job, or is he acting out the classical role of heroic knight in shining armor coming to rescue damsels in distress?

- Is Sammy really all that upset that he now has no job?

- Why the heck are those girls in the store "in nothing but bathing suits" (142), and why is everyone making such a big deal out of it?

Note: for that third question I actually wrote down a note, a quotation from the story; I am ahead of the game. WOOT!

I could probably come up with more quick questions, but this is plenty to start with. Now it's time to try to answer the questions. For this lecture, I will mainly look at question 1: "Is Sammy a hero or not?" It's time to go back to

look for patterns and peculiarities

Especially in shorter fiction (short stories, poems, one-act plays), if an author takes time to repeat something (a kind of image, a word or phrase, etc.), it is meant to stand out. Likewise, anything that is odd, weird, peculiar will pop out, and it is very rare that that is accidental. The author is saying, "LOOK AT THIS!"

If we are looking for evidence to answer our question, "Is Sammy a hero?" we need to think about what makes a hero. Here are some things that come to my mind:

- a hero is self-sacrificing

- a hero does not expect to be rewarded

- a hero has a "good" character

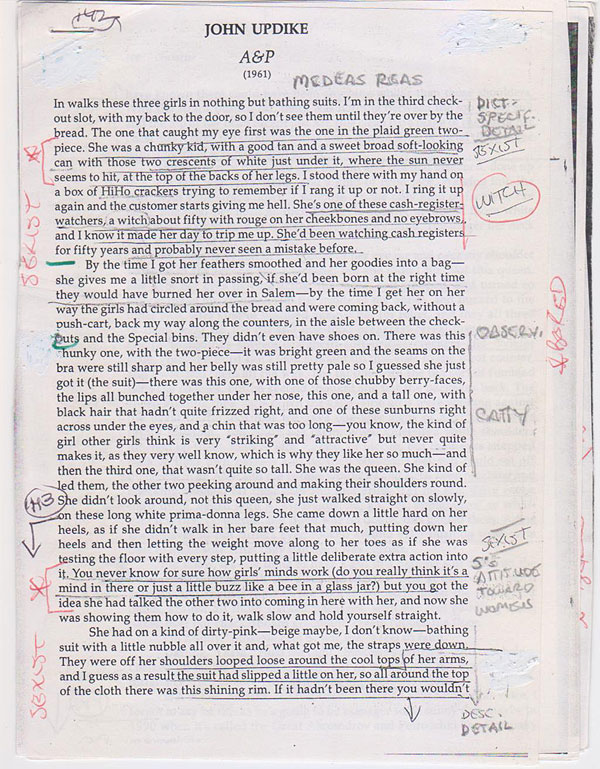

That's enough to get started with. Now the long part. I need to go back through the story, taking notes (this is very important; you will need these notes later) looking for things that are described/narrated that tell me if Sammy is self-sacrificing, expects no reward, has a heroic character. This story has a lot of material that addresses these points, and here are my notes just for one page of the story (I like to photocopy the story and then write on the photocopy, but feel free to mark up your textbook; you paid for it):

That is a lot to work with already, and there are examples like this throughout the story. Don't worry if you can't decipher my sloppy writing and abbreviations; I will explain examples in a bit. If your notes are sloppy, that's fine. Just be sure they make sense to you, and be sure you have enough notes--more is (usually) better.

Just on that first page, there are several patterns that help answer some of our questions; it is time to fill in lists that relate to the qualities I am looking for and tie them to annotations (highlights, underlining, marginal notes) I made on the story:

a hero has a "good" character

Sammy is a sexist; he complains about McMahon checking out the girls, but he's looking at their flesh: "She was a chunky kid, with a good tan and a sweet broad soft-looking can with those two crescents of white just under it where the sun never seems to hit, at the top of the back of her legs" (142).

He is even more sexist when he says, "You never know for sure how girls' minds work (do you really think it's a mind in there or just a little buzz like a gee in a glass jar?" (142)--he is saying girls have no brains!

He is in a service job, but his service is lousy, and he is disrespectful to customers; he calls one woman a witch: "She's one of these cash-register watchers, a witch about fifty with rouge on her cheekbones adn no eyebrows" (142). Later he is going to call customers "sheep" (143, 146), "house slaves with varicose veins" (143) and "pigs in a chute" (146). He doesn't seem to have a very good character.

a hero is self-sacrificing

I am not going to go through all of the examples; you can do that on your own. Here is a quick run-down, though: Sammy does not really like his job, and he did not seek it out in the first place (his parents got him the job), and it is not as if he will never work again. Find quoted examples of each of these statement.

a hero does not expect to be rewarded

Again, you can fill in this section, but there are several examples showing he is disappointed he is not going to get a date or a kiss or at least recognition: "The girls, and who'd blame them, are in a hurry to get out, so I say "I quit" to Lengel quick enough for them to hear, hoping they'll stop and watch me, their unsuspected hero" (145).

So far, I am building a pretty strong case for "Sammy is NOT a hero," and the list will grow as I find more examples from the story. Is there anything in the story that supports the other position--"Sammy is a hero"?

Even though he doesn't really like it, Sammy does give up his job, and his parents will probably yell at him, and he won't have gas money to take Peggy Sue to the drive-in until he gets another job.

And then there is the peculiar (remember, we are also looking for things that are peculiar) last line of the story: "and my stomach kind of fell as I felt how hard the world was going to be to me hereafter" (146). This doesn't even make much sense; it's melodramaatic, and Sammy is young, but quitting this job will not destroy his life. I could ignore this or try to make sense out of it. It's best not to ignore it.

First, the story is a flashback to an earlier time. We know this because Sammy says, "Now here's the sad part of the story, at least my family says it's sad but I do't think it's sad myself" (144). Sammy can't know his family's reaction unless the story is being told after the events he describes. Those events end before he goes home. That means he has had some time (how much?) to discover "how hard the world was going to be." To find out why it was hard, we should go back to that key moment when Sammy quits. Lengel knows Sammy is being rash, tells Sammy he will feel this for the rest of his life and that he does not really want to do this. Sammy thinks, "It's true. I don't. But it seems to me that once you begin a gesture it's fatal not to go through with it" (146).

So what has just happened? Sammy shows he has integrity. He makes a gesture, and he does not weasel out of it. This is the event he is looking back to where he knows he will live life as a person who keeps his word, and that is harder than not following through.

so is Sammy a hero?

My short answer is, "Yes." He is a rare person who will live his life with integrity. I've taken enough notes above to make the case for that.

so my thesis should be...?

The word tricky will come back in play this week.

After taking all of my notes, on all of my questions, I have to settle on a topic and devise a thesis. The thesis is my subject plus the point/claim I will attempt to prove about my topic. The subject is the author and story title, and the point/claim is the conclusion I arrived at about Sammy's being a hero or not. It will look something like one of these:

In John Updike's "A&P," the main character, Sammy, is a hero.

In John Updike's "A&P," the main character, Sammy, is not a hero.

Why did I write both positions when I told you already I think the story is about a hero?

There is not necessarily one right answer. I will look over my lists. The list showing he is sexist, disrespectful, bored, disinterested in his job, wishing for recognition will be a very long list with lots of examples. I can easily get a paragraph on each of those points. This lists suggesting he is a hero is really short. Can I get a four-page paper out of that? It is possible, but it will be hard. My inclination is to make life easy for myself (I guess I am not like Sammy), so I will probably select the following:

Although Sammy, in John Updike's "A&P," does give up his job when he feels Lengel is embarrassing three customers, his actions are not really heroic.

I've added the opposing position with my "Although" statement, and I've clarified my position with a little more detail. Note that the author and title are both in the thesis. It is clear what point I am going to develop and illustrate in my paper, and that point will be the focus of the whole paper; I will not take both sides. Could you take the harder side? Of course!

on to the essay (this lecture is nearly done...*whew*)

Now you take the material from your notes, sort it into meaningful categories (Sammy is a sexist; Sammy is disrespectful, etc.) and build your paper using the OBSERVATION-QUOTATION-EXPLANATION formula. After your paper's opening (which should be livelly, if possible, and should relate to the thesis somehow), you will put in your thesis. Then you will suppport that thesis with various claims (obervation) which you back up with quoted/documented examples from the text (quotation) and then transitoinal sentences taht explain how those examples fit and then lead on to your next point (explanation).

I call it a formula, but it's really more of a general guideline. It allows you to get enough of your own thinking into the discussion/essay, and it shows that you can support your conclusions with evidence (and know how to document that evidence).

If you would like to see what the beginning of an essay on "A&P" would look like, click on this link (file is a .pdf document), and it is in MLA format.

![[schedule]](button12.gif)

![[discussion questions]](button44.gif)

![[writing assignments]](button41.gif)

![[home]](button21.gif)