Now where would I shelve this?

The modestly-popular spoof comedy Not Another Teen Movie parodied not just one movie but an entire movie trend--the teen movie; the title refers to the glut of teen movies produced (and still being produced) in a relatively short time. With a string of "brat pack" movies--Joel Schumacher's St. Elmo's Fire, John Hughes's The Breakfast Club and Sixteen Candles, Howard Deutch's Pretty in Pink--, it became clear that teen angst could sell tickets. Observant Hollywood moguls (or perhaps accountants) saw the potential and began pushing out movies like Get Over it!, Bring it on, She's the Man, High School Musical--pictures that follow a predictible formula that appeals to teen audiences and fills theatres and sells DVDs.

When we group books or movies or other art forms by type or formula or trend, we often call that a genre (originally French for "type" or "class"). To some extent you can think of this as the section where you might shelve a DVD at Blockbuster, though some categories (Foreigh, Special Interest) are really not genres as much as they are grab-bags for large numbers of movies that might not fit in a more specific niche. And some larger genres (Crime, for example), can be broken down into smaller sub-genres (film noir, the gangster film, the heist picture, and so on). And genres such as Teen Movie migh show up in more than one area--most are in comedy, but you would be more likely to find St. Elmo's Fire in the Drama or Romance sections.

So genre (type) study is pretty flexible, and as the semester moves on, we will be looking at a handful of the most popular genres to see what qualities make up different types of literature and film. We don't have time to cover them all. A good starting point is with Chapter 5 of our textbook; Bernard Dick gives a solid overview of some of the major (and a couple of minor, such as The Reflexive Film) film genres. Most of these can be applied to literature as well (film noir, for example, is an offshoot of the serie noir detective stories that appeared in popular crime magazines; we'll look at that more closely when we discuss the detective genre). This week we'll look at some highlights of a few of the more popular genres we won't have time to cover in the remaining weeks.

The Hollywood Musical: "Puttin' on the Ritz" --Irving Berlin

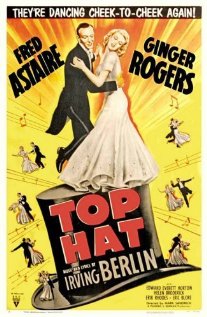

Of special interest in the history of films (not literature) is the Hollywood musical because this is one of two film genres (the other is the western) that was uniquely American. The 1930's-1950's was the most lively period for the Hollywood musical. Many films (such as Lloyd Bacon's 42nd Street (1933, noteworthy because this was the first Busby Berkely-choreographed musical), were really elaborate Broadway reviews with thin plots (typical stories involved a young woman who fell in love with a stage star or a worried producer who needed to scrape up some more money to put on his show). The genre created huge stars. Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers made a string of hits--Flying Down to Rio (1933), The Gay Divorcee (1934), Top Hat (1935), Swing Time (1936), Shall we Dance (1937), and so on--packed theaters with their amazing dancing and wry humor. Bollywood...renaissance in the 21st century...

Of special interest in the history of films (not literature) is the Hollywood musical because this is one of two film genres (the other is the western) that was uniquely American. The 1930's-1950's was the most lively period for the Hollywood musical. Many films (such as Lloyd Bacon's 42nd Street (1933, noteworthy because this was the first Busby Berkely-choreographed musical), were really elaborate Broadway reviews with thin plots (typical stories involved a young woman who fell in love with a stage star or a worried producer who needed to scrape up some more money to put on his show). The genre created huge stars. Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers made a string of hits--Flying Down to Rio (1933), The Gay Divorcee (1934), Top Hat (1935), Swing Time (1936), Shall we Dance (1937), and so on--packed theaters with their amazing dancing and wry humor. Bollywood...renaissance in the 21st century...

The middle of the 20th century saw a massive re-working of the musical with the works of Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hamerstein II. Richard Rodgers was already extremely successful in his musical collaborations with Lorenz Hart (who died in 1943), but the team of Rodgers and Hamerstein is likely better known today. The musical of Rodgers and Hamerstein works were tremendous hits on Broadway in the 1940's and 50's, and most reached massive audiences when they were translated to film. Most of the titles will be familiar (I wouldn't be surprised if you started humming "Surrey with a Fringe on Top" or "The Sound of Music"), and many of these works are now the staples of school theatre; the stories are formulaic, yes, but the formula is a winning one that still pleases audiences. Their catalogue includes such works as Oklahoma! (1955, these are film, not play, dates), The King and I (1956), South Pacific (1958), The Sound of Music (1965).

In the U.S. the musical's popularity waned in the 1960's and beyond with some interesting exceptions--musical comedies, romances, dramas driven by popular music. Without Elvis Presley Jailhouse Rock (1957), and a string of other Elvis movies, would not have been such huge successes. We still see this in movies such as 8 Mile, which would not have attracted as much notice without Eminem in the lead. Saturday Night Fever would hardly have been the phenomenon it was if the disco lyrics and storyline did not mirror the popular music tastes of 1970's audiences, and The Rocky Horror Picture Show gives audiences the ultimate in popular culture as midnight showings sell out because the people (the populi) becomes part of the show. And now there are cross-overs with teen movies (High School Musical, for example) which appeal to younger audiences weaned on The Disney Channel (in 2006 the most popular show on regular cable was Hannah Montana).

Even though the popularity of the traditional musical is certainly not gone, it is also not such a mainstay of movie houses as it was sixty years ago), has lessened in the U.S., it is still popular elsewhere. It would be hard, here, to ignore the nation whose film industry has overtaken Hollywood in scope, production, popularity--India. The Hindi cinema has been strong since the 1940's, and by the 1970's the film center of Bombey (Mumbai) became so dominant that it was dubbed Bollywood. One of the major influences on Bollywood cinema is the Hollywood musical of the 1930's-50's; India produces many much-loved romances and fantasies woven through with musical dance numbers that are as elaborate and bombastic as anything Busby Berkeley produced. Just a bit of this influence is seen in Danny Boyle's Slumdog Millionaire. The film, winner of eight academy awards, is British, but it was filmed in India and pays homage to the Bollywood dance numbers in the joyous, spontaneous "Jai Ho" dance number at the end of the movie. Does it make sense that common folks in a train station would simultaneouslly erupt into carefully-choreographed steps? Probably not, but musicals aren't really any more improbable than flash mobs, are they?

Even though the popularity of the traditional musical is certainly not gone, it is also not such a mainstay of movie houses as it was sixty years ago), has lessened in the U.S., it is still popular elsewhere. It would be hard, here, to ignore the nation whose film industry has overtaken Hollywood in scope, production, popularity--India. The Hindi cinema has been strong since the 1940's, and by the 1970's the film center of Bombey (Mumbai) became so dominant that it was dubbed Bollywood. One of the major influences on Bollywood cinema is the Hollywood musical of the 1930's-50's; India produces many much-loved romances and fantasies woven through with musical dance numbers that are as elaborate and bombastic as anything Busby Berkeley produced. Just a bit of this influence is seen in Danny Boyle's Slumdog Millionaire. The film, winner of eight academy awards, is British, but it was filmed in India and pays homage to the Bollywood dance numbers in the joyous, spontaneous "Jai Ho" dance number at the end of the movie. Does it make sense that common folks in a train station would simultaneouslly erupt into carefully-choreographed steps? Probably not, but musicals aren't really any more improbable than flash mobs, are they?

The Women's Film and The Guy Picture

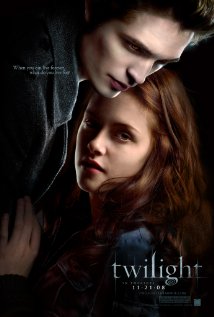

I know, I know; don't blame me for the genre title. This category, composed of women's dramas (movies such as King Vidor's Stella Dallas (1937) and Michael Curtiz's Mildred Pierce (1945, re-made as a TV mini-series with Kate Winslet in 2011) and romances has been a staple of predominately-female audiences. The serious stories of sacrifice and empowerment still exist in films like Steel Magnolias, but this genre has enjoyed an interesting transformation. Recognizing a large but changing audience, Hollywood has capitalized on a more-youthful market since the 1980's, and romantic teen comedies (such as Ever After, The Princess Diaries and 10 Things I Hate About You). The re-vamped genre sports a new name: "chick flicks"--the staple of teen date night (often the boyfriend would rather be watching Transformers 2 in 3-D, from the action/adventure sci-fi genre), but to make his girlfriend happy, he will sit through (and often find that he really enjoys) About a Boy, though maybe not Twilight.

![]()

hmmm...do these really look that different?

And what about the women's film complement--the guy picture? Just as women's films often cross genre categories (for example, many are comedies), Guy pictures quite often fall into the science-fiction or war movie or crime film categories. Guy pictures typically have one thing in common--action. Both movie posters above are dark with dramatic, moody lighting; both feature some otherworldly creature (vampire, alien); both posters have simple, unadorned text while showcasing faces pressed close together. But guy pictures are not the same as women's films. Where Catherine Hardwicke's Twilight tries to capture the romance and dark emotion of Stephanie Meyer's series, James Cameron's Avatar is like watching Halo (the vidoe game) on the X-Box 360. The emphasis is on explosions, cool technology, eye-popping visuals and ear-popping sounds. Guy pictures are about fast cars (Fast and Furious series) and elaborate toys (Transformers series) and comic books and video games come to life (Batman, X-Men).

The War Movie

War movies attempt to recreate military history (much as the SCA--Society for Creative Anachronism--members gather to physically re-create battles from the past); they also serve as propaganda tools during times of war and conduits for messages (often anti-war) the filmmakers want to share with audiences.

War movies attempt to recreate military history (much as the SCA--Society for Creative Anachronism--members gather to physically re-create battles from the past); they also serve as propaganda tools during times of war and conduits for messages (often anti-war) the filmmakers want to share with audiences.

At their heart the films share features with guy pictures and women's films--they are generally packed with actions and special effects (explosions often) and plenty of carnage; they also often convey the emotional costs (from the pathos of loss to the madness of sublimating humane and civilized behavior) of war. One powerful soviet film from the silent era demonstrate this blend of history and message, of action and emotion: Sergei Eisenstein's Battleship Potemkin. Based on an actual event, the movie shows a naval mutiny, riot, and resulting police massacre of citizens on the steps leading to the Odessa harbor. A haunting scene of a baby carriage bouncing down the steps is one of the most famous in early cinema, and it shows the cost to innocents of armed action.

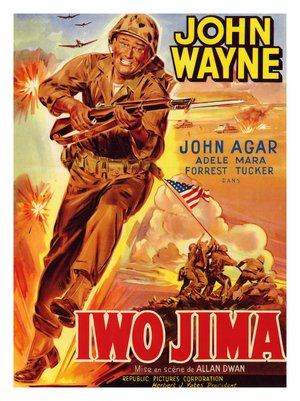

Eisenstein's movie could be classified historical social protest as much as (or more than) what we think of as a conventional war movie. By the first and second world wars, however, movies such William Wellman's melodramatic Wings (1927, the first movie ever to win an Academy Award for Best Picture) showed brave men fighting, and often dying, nobly to protect the nation and the wider world. A spate of movies starring the likes of John Wayne and glorifying U.S. military efforts in WWII helped to keep morale up during the 1940's (much the same as Cold War epics featuring James Bond besting insidious soviet and asian enemies were applauded by western audiences). This propagandizing and nationalism is hardly unique to the U.S. During WWII Hitler had a massive film industry producing films in support of the Reich and demonizing the Allies. And I remember a Czech student of mine many years ago laughing at the mention of James Bond; it seems filmmakers on the other side of the Iron Curtain had the same sorts of super secret agent movies showing the righteous eastern Europeans triumphing over the corrupt and fearsome west.

The insanity of war is a huge subject in post-Vietnam War movies. As a reflection of a relatively dove-ish turn in America in the past forty years, movies such as Oliver Stone's Born of the Fourth of July, Francis For Coppola's Apocalypse Now and Stanley Kubrick's Full Metal Jacket replaced the gung-ho movies of WWII and the Korean conflict. More recently, however, the trend in Hollywood is to show war as dangerous and disturbing while supporting U.S. the troops (individuals have supplanted the cause in films like Ridley Scott's Black Hawk Down and Kathryn Bigelow's The Hurt Locker. An interesting throwback to the 40's-style war movie is Jonathan Liebsman's recent Battle Los Angeles where a gallant cadre of infantry square off against aliens from another world rather than aliens from another country. Once again the enemy is displayed as less than human; in this case, though, the depiction is quite literal.

The Costume Drama

The first costume drama I remember watching (on television; yes, we had television in the 1950's) was Michael Curtiz's Captain Blood (1935, starring Errol Flynn and Olivia de Havilland). Here's how IMDB describes the plot: "Arrested during the Monmouth Rebellion and falsely convicted of treason, Dr. Peter Blood is banished to the West Indies and sold into slavery. In Port Royal, Jamaica the Governor's daughter Arabella Bishop buys him for £10 to spite her uncle, Col. Bishop who owns a major plantation. Life is hard for the men and for Blood as well. By chance he treats the Governor's gout and is soon part of the medical service. He dreams of freedom and when the opportunity strikes, he and his friends rebel taking over a Spanish ship that has attacked the city. Soon, they are the most feared pirates on the seas, men without a country attacking all ships. When Arabella is prisoner, Blood decides to return her to Port Royal only to find that it is under the control of England's new enemy, France. All of them must decide if they are to fight for their new King."

The first costume drama I remember watching (on television; yes, we had television in the 1950's) was Michael Curtiz's Captain Blood (1935, starring Errol Flynn and Olivia de Havilland). Here's how IMDB describes the plot: "Arrested during the Monmouth Rebellion and falsely convicted of treason, Dr. Peter Blood is banished to the West Indies and sold into slavery. In Port Royal, Jamaica the Governor's daughter Arabella Bishop buys him for £10 to spite her uncle, Col. Bishop who owns a major plantation. Life is hard for the men and for Blood as well. By chance he treats the Governor's gout and is soon part of the medical service. He dreams of freedom and when the opportunity strikes, he and his friends rebel taking over a Spanish ship that has attacked the city. Soon, they are the most feared pirates on the seas, men without a country attacking all ships. When Arabella is prisoner, Blood decides to return her to Port Royal only to find that it is under the control of England's new enemy, France. All of them must decide if they are to fight for their new King."

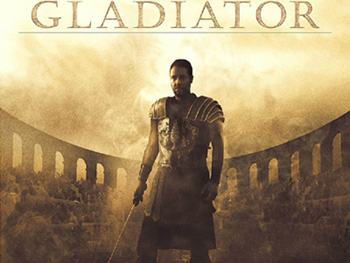

If that sounds a bit like it would fit in the "guy pictures" genre above, well, it would. Most costume dramas can fit into other genres as well--romance, war, and so on. What distinguishes them is the elaborate re-creation of a different historical period; the background (exotic sets, period costumes and objects, oddities of accent and gesture, historical detail) often plays as large a role as the story and actors in transporting audiences into the movie reality. Captain Blood had pirates, pitched sea battles, sword fighting, swinging from masts, a hero with dash and swash and bravado. And this film was (and is) certainly not alone.

To get a sense of how popular this type of picture is, you might want to search how many versions of Robin Hood have been made (there's have been multiple television series even); then check Zorro (don't overlook the foreign versions) and The Three Musketeers (there's a 2011 re-make); check out the variations of the King Arthur tale while you're at it.

The appeal of these pieces to the costume designer is obvious. What they offer audiences is multi-fold. Clearly they transport the viewer to a different time and place (one of the goals of all story-telling); shopping at Albertson's can be rough, but it's not the same as facing down trained fighters in a gladiatorial arena. They also tap into the child/play part of the viewer that may be deeply hidden but which is still waiting to get out and play pirates or princesses or Spartan soldiers. Most have epic sweep and drama, and the action is often showcased by a likeable hero who has cunning and wit and style. They are also generally way over the top and lend themselves to parodies (something the genre shares with horror movies), such as Mel Brooks's Robin Hood: Men in Tights and Jason Friedberg and Aaron Seltzer's Meet the Spartans. Disney's Pirates of the Carribbean franchise is not so much a parody of the pirate film as it is a humorous and graphically-stunning homage to the sub-genre, but it would not exist without the inspiration of movies like Captain Blood.

![[schedule]](button12.gif)

![[discussion questions]](button44.gif)

![[writing assignments]](button41.gif)

![[readings]](button13.gif)

![[home]](button21.gif)