glossing the text & critical thinking

In general, when you read college texts (articles, textbooks, literary works, etc.), you are required to apply different analytical skills to the reading than you normally do when you read a popular novel or watch your favorite T.V. sitcom. Most popular recreational reading ends with your discovery of whodunit or whether or not the couple will marry or if the treasure has been lost forever. Reading and thinking critically demands that you read, note, consider, and often re-read the material to figure out exactly what ideas the writer is expressing.

If you are expected to discuss or write about a complex reading, which you have to do when you take an essay exam (often a mid-term or a final), or write an out-of-class essay, the teacher will probably not just want you to answer simple fact questions ("What year was the film The Exorcist made?").

Your teachers also don't really want your unsupported opinions ("Was Tobe Hooper's The Texas Chainsaw Massacre a good movie?"). That does not demonstate your ability to analyze, to figure things out.

Your teachers DO want to see how you think, not just what you can memorize. Questions will be more open-ended and will allow you to demonstrate that you understand the point of what you are reading; they will require you to support your conclusions with examples from the reading. If you were reading Stephen King's "Why we Crave Horror Movies," from his non-fiction book Danse Macabre, for example, your instructor might ask, "What does Stephen King mean when he says that horror movies help to 'Keep the hungry gators fed'?". To answer this, you would also have to explore WHAT KING MEANS when he says, in the same article, that we are all insane. You do not have to agree or disagree with his position; you have to EXPLAIN his position.

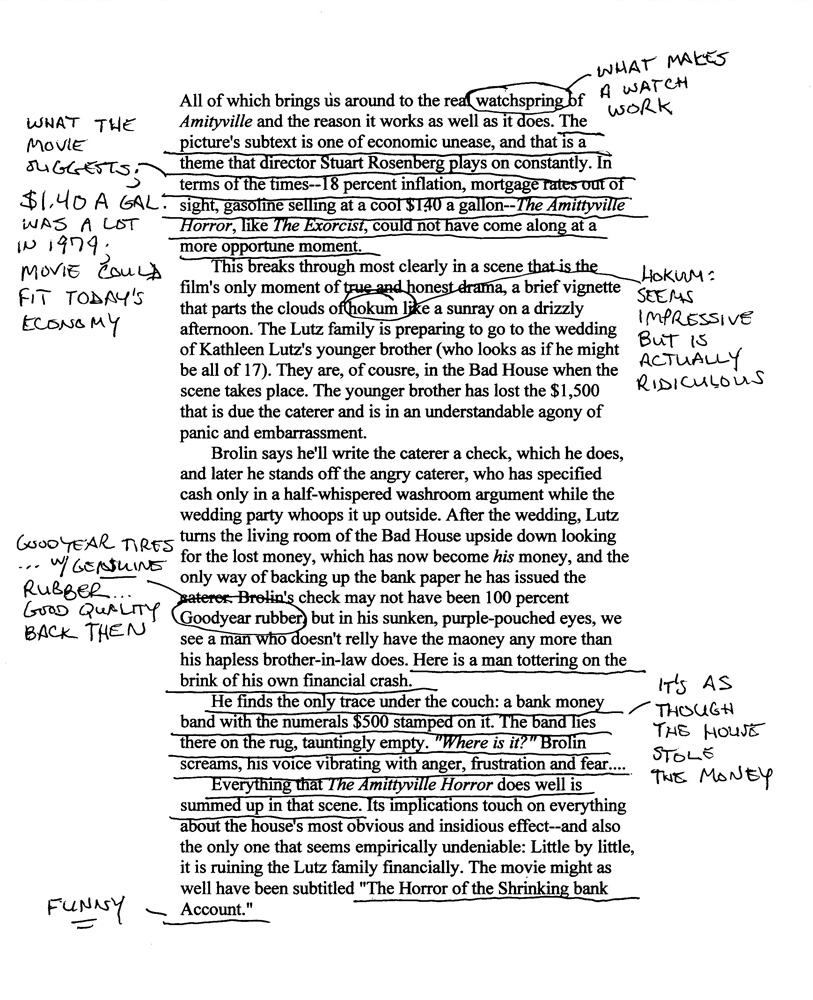

Since much of the reading you do in college is fairly sophisticated (in terms of both idea and presentation), you will want to develop a method of glossing the text that works for you. Glossing the text is just a fancy way of saying, "taking notes." Underlining, circling, highlighting, numbering items that correspond to notes in a journal, marginal comments--these are all workable methods of keeping track of items in your reading. Some of the kinds of things you should note are

- passages that you think are especially significant (that contain ideas which are key to understanding the author's point/argument)

- passages you question (either they challenge your thinking or you disagree with them because they are undeveloped/unsupported in the work)

- words, phrases, references (allusions) that you are not familiar with; you really do need to look these up to fully understand what the author is saying

- anything that you think stands out, that is unusual (perhaps an ironic passage, an novel comparison, an especially effective example)

The goal here is twofold: first, you want to extract as much from your reading as possible (after all, how can you justify agreeing or disagreeing with something you don't really fully understand?); second, you want to be more aware of how other writers communicate so that you can use some of the techniques in your own writing.

Review at the sample glossed (annotated/marked-up) copy of "In New Mexico" (which is on reading list); it is on Etudes under Resources > Readings. You can see what a typical marked-up paper looks like.

Tip: I understand if you do not like marking up your books (and you should never mark up a library book); an easy solution is to print-out or photocopy the reading you are working on and marking up the printout/photocopy.

ok, let's give it a try; we can use the practice

Stephen King's "Why we Crave Horror Movies" is an attempt to validate some horror movies as a serious art form. In his essay he lists a number of things that the superior horror movie gives to the reader; he discusses social, psychological, artistic elements in a number of films.

In this section of his essay he shows how the 1979 version of The Amittyville Horror, a haunted house thriller, works because it represents, symbolically, the social and economic situation of it's time. In essence, the film serves as a window through which viewers can see just what was disturbing to a culture with a troubled economy in the late 1970's.

In this section he suggests the horror n the movie is not a result of monsters and violent death. If there is a monster, it is the house itself that is falling apart, plagued with mysterious swarms of insects, draining the bank account of the owners. As one annotation suggests, this could fit the economic downturn of the 21st century. The housing crisis, with property values falling, people being evicted and losing life savings because the house takes up more money than they can earn--this is the horror of Amittyville.

you have done your annotation...now what?

The first part of this lecture, along with some of the reading from your handbook, asked you to look closely at the texts you are assigned, to ask questions, look things up, draw conclusions, attempt to understand someone else's unique thinking, assess the argument being posed, and imagine how the techniques another author uses to communicate could be incorporated into your own writing.

Yes, that's a lot, and it means reading college texts can sometimes be time-consuming and challenging

Ideally, the experience is pleasurable, but "pleasurable" means different things to different people. At the very least, the material assigned should get the critical thinking juices flowing or, if nothing else, share some information that is necessary for whatever course you are taking. In English classes, the subject is very changeable (we read about wrapping things one week, shopping the next, watching horror movies and playing video games and so on. But the goal is generally the same--to get you to analyze what you have read, to demonstrate that you understand (not agree or disagree but understand) someone else's thinking and see how he or she backs it up.

So once you have read a work and taken notes on it to try to fully understand it, you may be asked to demonstrate your understanding. This is often done in the form of a mid-term or a final exam, but it can also be oral (in a speech class, for instance) or in a more expanded sort of essay writing (in class or at home). For the online class, your Discusion Board discussions ask you to write very specifically about the essays you've read. You are encouraged to include personal examples (not opinions but actual examples / experiences) and relate the topic to other things you have studied (in school or on your own), but you are also required to demonstrate that you have analyzed (picked apart and considered) the reading itself. This analysis requires three things: observation / quotation / explanation.

5. observation / quotation / explanation integrating quotations into your essay

I am not a huge fan of formulaic writing. If students at this level trot out the five-paragraph formula that was designed for remedial composition, then their grades will not be stellar. Look at the more organic ways real writers write (get some ideas from the readings in our text). However, for analyzing things that you read, this method works especially well.

Research papers (more on that in future lectures) always require you to incorporate material from outside sources which you document both in the paper and on a Works Cited page at the end of the paper. But using source material which you document is not just for research papers.

Whenever you analyze what you read or hear or see, it's a good idea to use the observation / quotation / explanation formula:

OBSERVATION: Throughout your analysis you will make a number of observations (your ideas about what is being expressed by the other author). A lot of these will come from the notes you took, and these should be written in your own words.

QUOTATION: You then need to back up your thoughts by drawing specific supporting evidence/examples (the best examples are direct quotations which are appropriately documented with MLA standard parenthetical citations) from the author's work. Note: the material assigned in your handbook explains exactly how to properly use parenthetical citations.

EXPLANATION: Next you must explain how the material you've quoted illustrates your topic sentence or your thesis--how does it demonstrate your observation?

Of course, your essay will be woven together with the appropriate transition statements, but the greater part of your analysis will involve observation/quotation/explanation.

If you were writing an essay illustrating how Sherry Turkle's article "Why the Computer Disturbs" demonstrates "what disturbs is closely tied to what fascinates and what fascinates is deeply rooted in what disturbs" (Turkle 277), you might use the observation / quotation / explanation formula for a portion of your essay as follows:

I had a book on the cover of which was a picture of a little girl looking at the cover of the same book, on which, ever so small, one could still discern a picture of a girl looking at the cover, and so on. I found the cover compelling, yet somehow it frightened me. Where did the little girls end? How small could they get? When my mother took me to a photographer for a portrait, I made him take a picture of me reading the book. That made matters even worse. (Turkle 98)What disturbs her is this idea of infinity, a concept that can't be fully grasped by the limited facility of human logic. She goes on to explain that when she asked adults about the idea of infinity, about infinitely small, about endless repetition, adults did not have any answers for her "slippery questions" (Turkle 98). She then turns to computers which, she finds, are filled with these disturbing but fascinating ideas that are beyond simple explanation.

* Note: the first instance above (the longer quotation) uses the block format, which is indented as a block 1" or two tabs (twice as much as a paragraph indentation) and not surrounded with quotation marks; the shorter quotation near the end uses inline format (there are quotation marks around the quotation which is part of the regular flow of the paragraph). Both examples are from page 98, and it would be OK to eliminate the last name, Turkle, from the citations because she is mentioned before the quotations.

If you'd like to see another example, here is a Word document analyzing the first section of "Shopping and Other Spiritual Adventures in America Today," just click on the link . Of course the finished analysis would go on to discuss (and cite examples of) several of the other benefits she describes as well.

So backing up what you say (especially when you analyze a written work) often involves your interpretations (ideas, claims, understanding) that are supported and illustrated with material from the text you are analyzing.

IMPORTANT NOTE: notice that there are no "I" statements and no personal opinions in the above passage. The student is explaining the article and the author's ideas and signals those ideas with, "Turkle opens her essay..." and "She recalls..." and "What disturbs her..." and "She goes on to explain..." and "She then turns to computers which, she finds...."

This is something you should be incorporating regularly into your class discussions (remembering to also include actual examples and related ideas). When you do your research paper, you will use several texts (some written, some not) to back up your various claims. Be sure that you always introduce and explain this source material, and always remember to give credit to these other sources with parenthetical documentation.

![[101 home]](btnxanim.gif)

![[class schedule]](btnhour.jpg)

![[homework]](btnhwrk.jpg)

![[discussion]](btndisc.jpg)