faster!

"Now, here, you see, it takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place. If you want to get somewhere else, you must run at least twice as fast as that!"

The Red Queen in Lewis Carroll's Through the Looking Glass

If the last 50,000 years of human existence were divided into lifetimes of about 65 years each, that would make about 800 lifetimes.

Of those, the first 650 lifetimes were spent in caves.

Only in the last 70 lifetimes has it been possible to communicate through the written word.

Only in the last 6 lifetimes have we had the printed word.

Only in the last 2 have we had use of the electric motor.

And within our current lifetime (the past 65 years or so) have he seen part of the world pass from agrarian to labor in factories and to so-called white-collar labor of sales, administrators, educators, communicators, engineers, computer specialists, and so forth.

so what does any of this have to do with us?

The first 1/2 of World Literature encompasses a massive amount of human history--from the earliest creation myths, to the great epics (Gilgamesh, The Odyssey, etc.) of what we often call Classical Literature (ancient Greek and Roman literature figures most prominently in the Western world), past the dark ages and through the long middle ages where we have chivalric romances and religious epics, and into the Renaissance (the time of Cervantes and Shakespeare). Arguably it's too massive a field to handle; we can only take a taste.

The second 1/2 of World Literature, by contrast, looks at a realitively short period--the past few hundred years. We begin with The Enlightenment (aka The Age of Reason, aka The Neo-classical Age) which runs from about 1660-1770, right before the American and French Revolutions, and we end now, with contemporary literature.

But the acceleration noted in the sidebar makes this seemingly-uneven division reasonable. The volume of work surviving those first tens of thousands of years is small compared to the huge body of work produced in the past few hundred years. The degree of sophistication, the speed with which human beliefs, ideas and issues have changed in this short period is amazing.

The big questions are still the same:

"What's it all about? What is the meaning of life, the universe, and everything?"

"How does a person live a good life?" (with all definitions of "good" being applied)

Ten-thousand years ago people knew the answers; at least most didn't dwell on the questions too much. Most people had little leisure time to think about it. Most people were still slaves or, at the very least, working 16-hour days just to eke out enough food to survive. They were told what to think, to believe. They believed Phan Ku or Yahweh or Ulgen created the universe; they followed accepted codes of behavior. Socrates, Lao Tzu, a handful of others had time to dream and philosophize.

For good or ill education and the printed word changed all that. Nowadays we all think, so much that it prompted humorist James Thurber to quip, "Let your mind alone." But most people don't. We question, consider possibilities, try to satisfy our curiousity. And the numbers of different answers to those key questions about existence and meaning and living rightly have come fast and furious in these past few centuries.

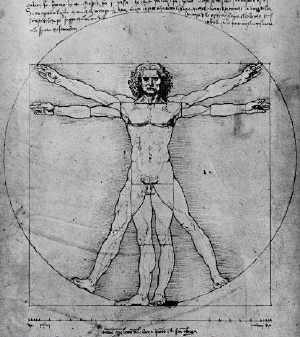

An apt (though certainly not the only) model for the Renaissance is Da Vinci's sketch "Man: the measure of all things" (see illustration at top of this page).

The focus was increasingly on the human reach, human life, the value of individuals. The architecture of the Renaissance moved from the heavenward-pointing Gothic arches of the middle-ages to graceful, comfortable curves designed to fit the human scale. Individual ideas replaced some of the dogmatic thought of the past.

By the 17th century, some felt that the human mind could ultimately unlock all of the cosmic mysteries previously reserved for religion.

the age of reason

The Age of Reason (also known as the Neo-Classical Period because people looked back to the values and order of Classical art and literature, also known as The Enlightenment because thinkers imagined they were, well, enlightened) was a short period. It was marked by huge change and a mixture of acceptance and resistance to that change, and this duality presented some dilemmas for philosophers, writers, leaders of the time who imagined they had some grasp of universal order but who found blind optimism balanced by skepticism and rational behavior overshadowed by war, cruelty, political and religious turmoil.

The 15th and 16th centuries had seen many scientific breakthroughs--notably, Copernicus' recognition that our system is heliocentric not geocentric, Galileo's work with the telescope, Kepler's theories and validation of Copernicus' work. This was also the era of world exploration; it ushered in a whole new way of viewing man and his relationship to the world.

Scientific breakthroughs inspired new philosophical ideas. Bacon and Hobbes in England maintained that method is the key to knowledge. They suggested that inductive logic and the scientific method could be used to understand the nature of man and society. On the continent Descartes, Spinoza, and Leibnitz were also influenced by progress and the success of science and mathematics. Their emphasis was on the rational capacity of the human mind, which they considered the source of truth about man and the world.

Deism (the idea that God is removed from creation) allowed some to dismiss the problem of creation itself and move on to the idea the what was created can be known as long as mankind hones the scientific method and develops increasingly sophisticated tools and models. The mystery of the universe was, thus, expressed with a short analogy:

Imagine that the captain of a ship lands on a very primative island and finds a group of primitive people not before touched by advanced civilizaton. The ship's captain gives the tribal leader his pocket watch as a gift. Never having seen anything like it before, the leader assumes the watch is magic, supernatural; he takes the sacred relic and creates myths and legends about the miraculous object and the amazing beings that brought it to his island.

Of course it's just a watch. If the tribe had sufficient tools and training, they could mass-produce the things. Lacking that scientific and technical background, they imagine the watch to be a gift from the gods. Note: you may want to rent The Gods must be Crazy to see a send up of this idea.

The British empiricists (Berkeley, Locke, Hume) called into question many of the premises of the rationalists. Locke implied skepticism insofar as he insisted that knowledge is based on sense experience and that substance reality (what Plato referred to as "forms") could never be known. Hume stated that all we really know is "impressions." Berkeley (famous for his Esse est percipe--"to be is to be perceived"; he's also the "if the tree falls in the forest..." guy) suggested all of our knowledge depends on sensory experience. These three emphasized the limits of reason and the ability to know reality beyond our perceptions.

In relgion the Jansenists were duking it out with the Jesuits (who were out Christinizing the new worlds). The Jesuits (headed by Ignatius Loyola) suggested that through good deeds (acts of conscious human will and reason) people could earn salvation. The Jansenists (named for the Dutch cleric Jansen) believed in predestination. They suggested that, doomed by Original Sin, people could only be saved through grace; human will and action and reason had nothing to do with divine justice.

In politics as the Western world was heading eventually toward bloody revolution, there was the age of absolute monarchy. France was the center of the Western world in the 17th century. Louis XIV (the sun king) stated, "L'etat c'est moi!" ("I am the state!"), and the essayist Hobbes wrote in his "Social Contract" that without the transfer of power from the people to the state there would be anarchy. Louis XIV's assumption of total control was seen as the head (reason) taking control over the passions that less aristocratic individuals were likely to give in to.

And in the salons of Paris--the social centers of the Aristocracy--the doctrine of proprietesse (polished manners, tact, reserve, understatement, prudence, decorum) was urged. Of course the irony of this all-too-rational facade presented by the French aristocracy is that behind the closed doors of the salons one found lust, greed, treachery--every passionate element the social elite pretended to abhor.

If you read Jean Racine's Phaedra (which is in our text). All of these opposites come crashing together. Borrowing heavily (in both form and content) from the classics, Racine produced a modern version of the Greek queen Pheadra who fears her husband Theseus has perished and lusts after his son (by a prior marriage) Hippolytus. Hippolytus rejects her advances, and Theseus, not dead, is seen returning to Athens. Pheadra feels guilty, confused, desparate. Her confidant, Oenone, convinces Pheadra that the appearance of virtue is more important than virtue itself and tells Theseus that Hippolytus has tried to rape the queen. In a rage (and after a few plot twists) Theseus curses Hippolytus, who is killed. Eventually Oenone commits suicide and Pheadra confesses her guilt and drinks poison. Theseus is grief-stricken over his son's death but is glad to be rid of the treacherous Oenone and Pheadra.

The play is shocking not because of the considerable body count but because Pheadra (who should practice proprietesse as should all aristocratic ladies and gentlemen in the court of Louis XIV) gives in to her animal lusts. She lets emotion cloud her reason. And like many of the actual ladies and gentlemen in the court, she presents a facade of virtue without actually living a virtuous life.

It's a mess.

And it's against this very confused/confusing background that Voltaire paints his wonderful satire, Candide.

![[schedule]](button12.gif)

![[discussion questions]](button44.gif)

![[writing assignments]](button41.gif)

![[readings]](button13.gif)