life as an insect in the modern world

This seems like a good spot in the semester to digress a bit, though just a bit.Metamorphosis

Roger Ebert gave Steven Soderbergh's Kafka a thumbs down on Siskel and Ebert: At the Movies and just two stars in his Chicago Sun Times movie review column.

It's not that Ebert doesn't like Soderbergh's work in general; he even put a number of his films in his Top Ten lists, among them Sex, Lies, and Videotape (1989), Erin Brockovich (2000), and Traffic (2000). He just did not like this movie.

Here are some of his comments from The Chicago Sun Times (published 2/7/92):

"Kafka" seems located within a set designer's nightmare. The movie takes place in a Prague more or less like the imaginary cities of Franz Kafka's fiction, and then it moves to an interior set that seems inspired by "Bride of Frankenstein," crossed with "Re-Animator."...

"Kafka" tries to avoid this problem [he's referring to problems of characterization in Orson Welles' "The Trial"] by being about the author rather than his characters, but as written by Lem Dobbs and played by Irons, Kafka is a fish out of water. He belongs lost in his existential reveries, and it is more than a little bizarre to see him transported into the Mad Scientist genre, climbing ladders over domes upon which are projected the interiors of brains....

Kafka, as subject or character, simply doesn't fit into the world of this film.

Hmmm...

This touches a bit upon our last lecture's considerations of fiction Vs. truth, illusion Vs. reality--just where do we draw the lines?

Kafka, the film, is about Kafka, the writer; it's just not limited to historical biography. The biographical bits are there--Kafka's hatred of his repetitious, make-work tasks in large, unfeeling institutions; his attempts to express himself through his writing but living on the outside of the literary world; his alienation from his harsh, military father who could not accept a son who wanted to pursue something so frivolous as the arts; the irony of the onset of death by consumption as he begins to find peace with some of his choices.

The other parts of the movie--the paranoid, canted, gothic shots; the chase through the mad laboratory; the tweedledee/tweedledum assistants in his office; even the shift from black and white to color and back to black and white again--all of these are expressive of Kafka's view of the world and of his feelings.

Ideas, thoughts, feelings are part of who we are. Soderbergh portrays a man who has difficulty accepting established truth and institutional reality. He's paranoid, afraid of "the system"; he sees the world as ominous, filled with conspiracies.

Certainly this sense of the dehumanization of labor in the early 20th century, the notion that humans driven by institutions are not humane, the alienation that the artist feels when he's misunderstood are all common themes in Kafka's writings; they also appear to have been common themes in his life.

I certainly wouldn't suggest that everyone will like Soderbergh's strange film; still, Kafka is on my recommended "to rent" list as we look at Franz Kafka's Metamorphosis.

OK, so I love movies

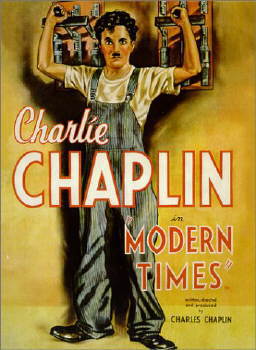

Modern Times (1936) is classic dystopian fiction; Charlie Chaplin plays a blue-collar Everyman whose job is to tighten nuts on some parts which whiz past him on an assembly line. Each man on the line has a task--hammering a piece or screwing down a part or tweaking this or that. It's mindless and monotonous. It's reminiscent of the drones in Fritz Lang's Metropolis (yes, another film) who trudge to their work stations and become cogs in some giant machine for long, arduous shifts. In that movie one character is a switch; he moves the hands of a dial from light to light to complete circuits, and when he collapses at his station, he's hauled away and replaced by another faceless drone. Likewise, Chaplin's character in Modern Times is dehumanized; he's only as valuable as the number of nuts he can tighten during his shift.

In a scene that surely influenced George Orwell's novel 1984, the bosses have installed giant two-way screens so that workers are constantly spied upon and yelled at when they try to take much-needed breaks.

It gets worse. An inventor demonstrates a machine that will allow workers to eat a full-course meal while standing up, still working on the assembly line. The bosses and the machines have taken over, and the average worker has been reduced to hands (or whatever part of the anatomy is accomplishing the menial task).

It's hard to say which is more dehumanizing--reducing a human to a mechanical part or imagining a human transformed into an insignificant bug.

This is the world of Gregor Samsa (gregarious, among people as he sells his wares from place to place, but alone--samsa).

He's a product of the Industrial Revolution and its reduction of labor to assembly-line work. His job is repetitious, without stimulation or satisfaction; he's one of millions of workers just grinding out hours of unfulfilling work while an elite few reap the greatest rewards.

In the scheme of things he is a cockroach or dung beetle (or vermin, depending on your translation). What makes the book so surreal is that in the book Gregor is literally transformed into an insect--he becomes the symbol.

And therein lies much of the humor and the horror of the novel. As he flattens himself to hide from his family, we can only wonder at the mechanics of a six-foot cockroach; it's a bit icky and ingenious at the same time. His attempts at communication are pitiable, but his mastery of his many legs is triumphal.

What's more important is that Gregor, for all his bugness, is more deeply human than those around him. His boss is mean-minded, accusing Gregor of stealing company funds when he's got a spotless record. His father is a malicious fraud, bleeding his own son for expenses which he could well earn himself and even stealing additional money for his own private nestegg. His mother is distant; she faints dead away whenever she sees him. Even the sister he's always supported eventually betrays him and wishes him dead. All the while Gregor holds on to his sense of duty, saying he'll just take a little nap and wake to get back to work; to his love of beauty while he sways rhythmically to the music; to his hope for possibility as he refuses to give up his cheaply-framed print of the lovely woman.

Much of this week's discussion will open up various interpretations of the novel, but at it's most basic level, it is a vision of how the institution grinds down the individual and how the individual is the enemy of the institution.

It brings the whole notion of progress under scrutiny.

And if you've seen all of the movies listed so far, try Terry Gilliam's Brazil.

![[schedule]](button12.gif)

![[discussion questions]](button44.gif)

![[writing assignments]](button41.gif)

![[readings]](button13.gif)