coffee-and-cigarette films

A personal loss of identity is the most desirable experience one can know.

- Marguerite Duras, discussing the theme of much of her fictionAt the end of the film it is as though, through them, all of Hiroshima is in love with all of Nevers, [and pre-existing differences of nation, race, history, and philosophy are] put into question by universal factors of eroticism, love and unhappiness.

- Marguerite Duras[In Hiroshima, Mon Amour] There is a similarity between the personal and the larger social tragedies, but they are not congruent. Ultimately the couple can identify on a personal level, but the larger social barriers are insurmountable.

- Alan Casty, Santa Monica City College

Of course the French New Wave is not new anymore, and tastes change. Students may find that the the semi-verite flavor of the camera work, the use of montage (the films often being composed by auteur directors in the editing room), black and white, a measured (slow) pace, and lots of talking are more suited for pensively smoking Gitanes and drinking thick cups of coffee than the fist-of-popcorn-with-32-ounce-Coke movies of the 21st century.

It's not Schwarzenegger.

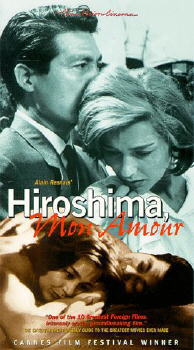

But the script that Marguerite Duras wrote in 1958 for director Alain Renais launched one of the most widely-praised films of all time. One reviewer called it "a thousand films in one." If there is little action, there is certainly no absence of thought in the movie: it's a love story, certainly; it's an anti-war protest that serves as an elegy for the victims of the bombing of Hiroshima, and it's "a grim picture of how everyday human relationships--even inside the same community--are deformed and made vicious by war" (Mack).

This week's discussion questions cover a lot of ground (the quotations at the beginning of this page should give you some useful ideas).

I'll just look closely at the movie's opening shot.

The film opens with an extreme close-up of shimmering skin (though it's not immediately apparent that it is skin). The screenplay describes

[As the film opens, two pair of bare shoulders appear, little by little. All we see are these shoulders--cut off from the body at the height of the head and hips--in an embrace, and as if drenched with ashes, rain, dew, or sweat, whichever is preferred. The main thing is that we get the feeling that this dew, this perspiration, has been deposited by the atomic "mushroom" as it moves away and evaporates.] (2505)

The "whichever is preferred" charges the viewer with interpreting what he/she sees. It's ambiguous, open to interpretation. The tight focus and closeness of the image are out of context for the viewer. We look for some clues to help us understand what we're seeing. The voices describe some of the horrors of the bombing of Hiroshima at the end of WWII. There are images of hospital corridors and evidence of the bomb blast pictured at the Peace Museum, newsreel clips showing the aftermath, the devastation.

Meanwhile, SHE says, "I think looking closely at things is something that has to be learned" (2512). SHE says she's seen everything; HE argues she's seen nothing. Perhaps they're both right. Like so much modern fiction this film is, on one level, looking beneath the surface of things, discovering implications, making connections, filtering information through individual consciousnesses (points of view) and conscience (belief). And once again the koinos kosmos (common view) is at odds with the idios kosmos (individual view).

As the camera pulls back we see the image of lovers, not radiated corpses. But the connection, the love/death, is already established in our minds. The love affair is shaped by the events of WWII in some way that we must discover along with SHE and HE.

HE discovers that SHE does indeed see; she shares his survivor's guilt, shares his sense of betrayal and despair. Her story of her love for the German soldier (with whom she identifies; eventually she will confuse the architect for that same German soldier) parallels the love of HE/SHE and is doomed for the same reasons.

It's a story of looking closely and even understanding what divides us, what has programmed us; at the same time, it suggests that the programming is so wedded to our being, that it's near-impossible to overcome it.

The camera moves; we have more information; death is replaced with erotic love. Still, the collision of images of devastation hang before our eyes. The lovers move through the film in a sort of dance, circling but never quite touching one another; the city (like the little Japanese woman near the movie's end) watches them and separates them. Hi-ro-shi-ma and Ne-vers-in-France (the larger communities) keep HE and SHE (the individuals) from ever joining one another.

![[schedule]](button12.gif)

![[discussion questions]](button44.gif)

![[writing assignments]](button41.gif)

![[readings]](button13.gif)