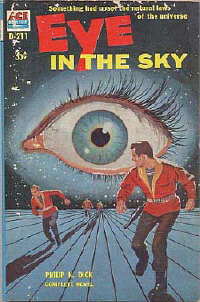

well doesn't the book cover just say it all?

Philip K. Dick is an acquired taste. He was never hailed for his technical abilities as a writer (in some of his more convoluted works whole plot threads wander off never to be found again), but he is considered by many writers as one of the most "important" and "visionary" writers of the late 20th century. Ursula LeGuinn called him our Borges.

One of the reasons for the occasional lapse in unity in Dick's works is the haste with which many were written. Eye in the Sky, for example, was written in just two weeks. In no small part this may be because Dick had to pay his bills.

This was just his fourth book (he wrote many). His first novel, Solar Lottery was published in 1955, and Dick, who'd written primarily short stories for magazines, said he was not proud that his work was lumped in with the then-marginalized science-fiction genre. Much of what was being produced at the time--stories about bug-eyed monsters, berserk robots, space damsels held at raygun point waiting to be rescued by muscled rocketeers--was formula fiction aimed primarily at adolescent boys. Not only did the field get little respect (even though there were heady works by Van Vogt and the Hoyles and others), there was very little money to be had. An ACE double (two books bundled back to back; the first book read from the front to the middle; then the books was flipped over and the second book was read from THAT front to the middle) novel earned him about $500, period. Yes, $500 had more purchasing power in 1955 (and 1957 when Eye in the Sky was published), but it was not big money, even then.

So he wrote what amounted to five fat volumes (his collected stories), a dozen mainstream novels, over thirty full-length science fiction novels, a children's novel, a screenplay (for his novel UBIK) and a few teleplays.

Money was nearly always in short supply. It's an irony (appropriate perhaps since Dick's work is thick with irony) that just as he was about to become wildly successful, with the film Blade Runner, based on his novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, nearly completed, he died. The film is dedicated to his memory. He'd sold the film rights to a story called "We can Dream you" which became Total Recall; since then Screamers, Minority Report, The Imposter, Paycheck have all been made into films (of varying success), and his long-optioned A Scanner Darkly is finally in production.

So what's the fascination with P.K. Dick?

Within the framework of his often-goofy plots (he has his share of rayguns and robots--replicants, simulacra--of flying cars and psionic powers and a fair amount of booze, drugs and sex--in the pulp tradition) he paints ideas. And his canvas is broad, containing politics, religion, philosophy, psychology, sociology, the paranormal, and even, occasionally, science.

At the heart of much of his fiction are two questions:

What is human (or living)?

What is real?

If you've seen Blade Runner or The Imposter you've gotten a glimpse of the first theme.

Eye in the Sky deals with the second, with what is/isn't real. Dick saw this novel as a parable along the lines of Plato's parable of the cave. He was certain that the idios kosmos (the personal view that each of us has) was not the same as the koinos kosmos (a shared world view or shared perceptions). This extends to physical/metaphysical questions about simple observations (quite possibly when we both see what we have been trained to call "red" one of sees what the other would call "green"--that sort of thing). In a more practical application, Dick is noting that our perceptions are shaped in large part by our conditioning (that's why someone on Iron Chef finds fish innards delicious while someone watching is gagging; it's why one person finds a political party reassuring while another finds it tyrranical; etc.).

In Eye in the Sky personal neuroses, psychoses, obsessions, conditioning all shape what each character perceives as real. Likewise, what we consider real, truths ("Roller coasters are dangerous" or "Roller coasters are fun") are largely based on our own fears and desires and upbringing. Following the bevetron explosion the controlling character's vision actually shapes reality for everyone else in the group; these other characters, in turn, are in a wigged-out funhouse of a world that does not match the idios kosmos they are familiar with. If you don't have OCD, imagine what the world must look like through the eyes of someone who has that disorder. If you do have it, imagine what the world must look like through the eyes of someone who doesn't. The experience would be totally foreign. And if people don't see the world the same as one another, then what does the world really look like? What is genuine? authentic?

Maybe the koinos kosmos (common world/cosmic view) holds the answer. However, Dick was obsessed with the notion that humans experienced mass hallucination (figuratively and literally), and he questioned why we believe what we believe not only as individuals, but also as groups. For Dick part of what we call reality is carefully orchestrated by powerful forces (often political entities; there's plenty of conspiracy paranoia in Dick's fiction; he was, after all, a writer during the McCarthy era). Repressive rules limit personal freedom and require us to hide or reject natural responses. Media saturation (ubiquitous advertising in The Minority Report, virtual reality [or is it?] in Total Recall) shapes tastes, even beliefs.

And science and history aren't much help; both change. The world (so we think) is not flat and not being orbited by the sun; Colombus, once considered a hero, is now considered a villain.

So like Candide and his buddies, the characters go through an ever-wilder series of episodes and disasters. And like Voltaire's short novel, Dick's is a sharp satire of many personal and institutional elements that make up our world. The characters are on a quest to find some wider truth.

Searching for this elusive truth, the protagonists finally settle on cultivating their own hi-fi shop.

Lecture 14b: Haruki Murakami - He doesn't like to be defined

well, to be fair, this is not really a lecture at all; it's a link to an interview

Haruki Murakami: "I'm kind of famous..." Daily Telegraph interview from 2004

Although he does not like to be defined or pigeon-holed, he says two of his greatest influences were Kafka (one of his books is called Kafka on the Shore, and one of his short stories is "Samsa in Love") and Garcia-Marquez. He may not be post-modernist, but he is definitely modern in his experimental style and subjects/thinking. Like many we have read in the latter part of the class, his works put is in doubt about what is real both inside his books and in the world we inhabit outside the books.

He is just a wee bit older than i am, but he is still writing, so he is the one "contemporary" author in the class, and one of the Paper 4 topic options and this week's Discussion topic options allow you to explore his unusual work. With those options in mind, I will list some of his works here that will give you lots to write about:

Hardboiled Wonderland and the End of the World

Dance, Dance, Dance, note: this continues some material from earlier works, but it can definitely be read by itself.

Kafka on the Shore

1Q84, warning: released in the U.S. as a single volume, it was originally a trilogy in Japan. So it is long. It is, however, that made Murakami famous outside of Japan.

The Wind-up Bird Chronicles

The Elephant Vanishes, note: this is a collection of short stories; you are welcome to write about one or two stories if you like.

This is not a complete list, but it's good for starters :)

![[schedule]](button12.gif)

![[discussion questions]](button44.gif)

![[writing assignments]](button41.gif)

![[readings]](button13.gif)