comedy, comedy?

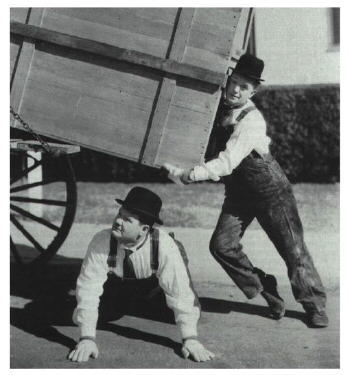

The second or third meeting of the live class I always show the Laurel and Hardy 1932 Oscar-winning short "The Music Box" Note: you are all welcome to stop by to watch the film if I'm teaching a live section and if you're schedules allow it. The film would make a wonderful text for a seminar on the theory of comedy--all of the elements are present.

The premise is simple: Mr. Laurel and Mr. Hardy have a moving company (basically, they have an old horse wagon, some block and tackle, and high hopes). A woman purchases a piano as a gift for her husband, and Laurel and Hardy are given the job of delivering the piano. They find the address, park their rig, and see that the house is at the top of several very long, steep flights of concrete stairs. They have to heft, push, pull, kick, haul that crated piano up the stairs. Like modern Sisyphuses, they nearly reach the top again and again only to have the piano clang and thump back down the steps to the street below. But they never give up; eventually they crest the hill, take a deserved rest, and are told that they didn't need to push the piano up the stairs at all, there's an access road that comes up the hill behind the house. The light dawns, and the two heave the piano back down the steps to their cart so they can drive it up the access road. The film isn't over at that point; if anything it gets more outrageous.

The comedy, taken literally, is painful, dark. It's filled with failure and injury (there's a scene where Hardy steps on a nine-inch nail that still makes me cringe). There is stupidity and cruelty (the boys are wrongly punished for giving a nasty baby-nurse a much-deserved kick in the seat of her pants). The physical strain on screen is repeated to the point of the audience's exhaustion.

So what's so funny about that?

A larger question might be, "What's so funny about comedy in general?"

Comedy is painful, dark, cruel. What makes us laugh is often the misfortune of others (it's not us for a change), nonsense, stupidity, mistakes, mishaps, monotonous repetition. There is also humor of wit and incongruity (there is a scene in "The Music Box" where the boys and a mad professor are in the middle of a pitched battle; the piano, a player piano, starts playing "The Star-Spangled Banner," and all three stop to salute--it's not very realistic, but the incongruity earns them a chuckle).

Though it's not all malice and pain. We do laugh out of a sense of relief that it is not us (this time) that the events are happening to. We feel free to laugh because the characters are characters, not real humans. They're made of rubber. It really is painful to watch Hardy walk, eye-first, into a board or fall headlong out of a window. But he bounces back; he's not bleeding. Within moments of stepping on that nail he and Laurel are tapping out some snazzy dance steps to the patriotic music playing on the piano.

Comedy is exaggeration, impossibility. It's also a means of taking healthy jabs at the flaws of the human condition. Satirical comedy pokes fun (often bitterly) at unfair, unfeeling institutions, and at the meanness that people see in others.

Three of the incidental characters of "The Music Box" are representations of the sorts of institutional characteristics we often fear and distrust (at least suspect). We see the baby-nurse out walking her charge. A babysitter is there to protect the innocent. She should have warmth, compassion, the instinct to protect. This sitter is mean and pushy, uncaring; she takes great joy in seeing the piano rumbling down the stairs (her fault). In the heart of every parent there is the fear that the sitter may be home ignoring or abusing the child (several Oprah segments centered around those home mini-cams that caught abusive nannies on video). Then the police officer, who should be there to protect and serve, to help those in distress and to evaluate situations fairly and judiciously, takes the nanny's side without listening to the entire story; he lays into Hardy with his billy club. Even the most innocent among us can have a sense of dread when a highway patrol car falls in behind us on the freeway, and there has certainly been much made of police corruption in the past decade. There is the professor. Arguably a professor represents reason, thought, a scholastic temperment. But this professor is a loud, brash, bully with a hair trigger; he seems out of his mind for most of the film. I've no further comment on that :)

By the way, the "Music Box" steps are still intact, though the area has changed a great deal. You can visit them in the Silverlake area of Los Angeles at 923-937 Vendome; the Way out West tent of the Sons of the Desert (the Laurel and Hardy Society), have placed a commemorative placque by the steps, and the city put up a special "Music Box Steps" street sign. The house across the street is still there, but the house at the top of the steps has long since gone. When the short was filmed, very little was built in the area; there were wide open lots on either side of the steps themselves. As you can see, in the current photo, there are now buildings right up against the steps.

By the way, the "Music Box" steps are still intact, though the area has changed a great deal. You can visit them in the Silverlake area of Los Angeles at 923-937 Vendome; the Way out West tent of the Sons of the Desert (the Laurel and Hardy Society), have placed a commemorative placque by the steps, and the city put up a special "Music Box Steps" street sign. The house across the street is still there, but the house at the top of the steps has long since gone. When the short was filmed, very little was built in the area; there were wide open lots on either side of the steps themselves. As you can see, in the current photo, there are now buildings right up against the steps.

on to Candide

We start our semester with Voltaire's comedy classic Candide. All of the elements of comedy are in this little book. It has wit and stupidity, relentless repetition and incongruity, intense cruelty (this is a very dark comedy) and elastic characters (most are miraculously not killed, against all odds, again and again), and very pointed satire. The editor of our text opens

Voltaire's Candide (1759) brings to near perfection the art of black comedy. It subjects its characters to an accumulation of horrors so bizarre that they provoke a bewildered response of laughter as self-protection--even while they demand that the reader pay attention to the serious implications of such extravagance. (1542)

Written near the end of the Age of Reason, when the ordered Western world was about to unravel with the American and French Revolutions, it is a blistering attack of the blind optimism and certainty that the rationalists voiced. If this was indeed an orderly world with a knowable plan; if it was "the best of all possible worlds," then why was there so much war, hunger, hatred, cruelty, sheer misery in the world?

The subject is terribly serious, and Voltaire uses several real-world examples (a massive earthquake, the insquisition, several European wars) as the backdrop for the adventures of Candide, Pangloss, Martin and the others.

He manages to keep his grim subject light by drawing upon all of the tricks of the comedic writer. A quick look at just the first few chapters of the novel show the range of comedy used to mitigate the real horrors in the novel.

As an exercise you might want to go over Chapter 1 and look line by line; you'll find different comedic techniques used in almost every sentence. Here are a couple of examples:

The old servants of the house suspected that he was the son of the Baron's sister by a respectable, honest gentleman of the neighborhood, whom she had refused to marry because he could prove only seventy-one quarterings, the rest of his family tree having been lost in the passage of time. (1545)

There is irony and exaggeration here: 1) the "respectable, honest gentleman" is certainly not above having an illegitimate son by the Baron's sister, and 2) the Baron and his family's requirement of marrying blue-bloods would be near impossible if a suitor were required to trace a noble family history back more than seventy-one generations.

A bit further down the page Voltaire writes, "The Baroness, who weighed in the neighborhood of three hundred and fifty pounds, was greatly respected for that reason" (1545). Of course her girth would suggest that she was from an aristocratic family since most common people were near starvation. Still, if anything her gross size would be an affront to those who were watching their children go without food; Voltaire is satirizing the excesses of the aristocracy when he suggests that gluttony is worthy of respect.

The philosopher Pangloss' explanation of the origins of breeches and castles and pork are silly, not profound as is Cunegonde's confusion of Pangloss and the maid's having sex in the bushes as a "lesson in experimental physics" (1546).

Chapters 2 and 3 are horrific; the body-count and carnage are graphic, and the torture of Candide impossibly extreme. Still, the off-handed presentation, the light comparisons and jolly tone create an incongruity that is a mainstay of comedy.

The sharpest digs, though, are reserved for those unrelenting optimists of the age who suggest that the butchery, savagery, meanness of the time were "necessary" for some greater good. One of the most famous examples of this satirical attack is in chapter 4 when Candide discovers that his old teacher has not died, as he suspected. After hearing that his beloved Cunegonde was raped and killed (he's wrong; she's not dead) and how the Baron's castle and troops were destroyed, Candide asks how Pangloss now appears before him as a beggar covered in boils, frail, with sunken eyes, rotten teeth and a hacking cough:

Pangloss replied as follows:--My dear Candide! you knew Paquette, that pretty maidservant to our august Baroness. In her arms I tasted the delights of paradise, which directly caused these torments of hell, from which I am now suffering. She was infected with the disease, and has perhaps died of it. Paquette received this present from an erudite Franciscan, who took the pains to trace it back to its source; for he had it from an elderly countess who picked it up from a captain of cavalry, who acquired it from a marquise, who caught it from a page, who had received if from a Jesuit, who during his novitiate got it directly from one of the companions of Christopher Colombus. As for me, I shall not give it to anyone, for I am a dying man.

--Oh, Pangloss, cried Candide, that's a very strange genealogy. Isn't the devil at the root of the whole thing?

--Not at all, replied that great man; it's an indispensible part of the best of worlds, a necessary ingredient; if Columbus had not caught, on an American island, this sickness which attacks the source of generation and sometimes prevents generation entirely--which thus strikes at and defeats the greatest end of Nature herself--we should have neither chocolate nor cochineal. (1551-2)

Of course there are numerous barbs in this passage: first, the line by which the syphilis was transmitted includes several religious and aristocratic individuals (obviously not bound by the rules of proprietesse that supposedly characterized this age); second, the light dismissal of the spread of veneral disease which was epidemic in Europe at the time and which would eventually kill millions; third, the notion that this horror was a good trade because the source--the explorers who visited the new worlds in the 15th-17th centuries--allowed Europeans to have chocolate and cocaine.

So Candide wanders the world gaining experience. His tutor consistently shows the "good" inherent in misery; Martin argues that nothing good can come of anything. As events pile up on events, Candide will have to make his own decisions, and by the end of the story he will speak one of the most oft-quoted lines of Western literature.

![[schedule]](button12.gif)

![[discussion questions]](button44.gif)

![[writing assignments]](button41.gif)

![[readings]](button13.gif)