storm and stress

Most Americans, if they think of Johann Wolfgang Von Goethe at all (by the way, the last name is pronounced more like "ger-tuh" than "goth"), think of him as the author of Faust. In Continental Europe, however, Goethe is known as "the Werther author"; rightly so, I think, because this little novel had much more impact on the style of life and literature in Europe than did Faust; it is also far more representative of The Romantic Era than Faust, which borrows heavily from the neo-classical.

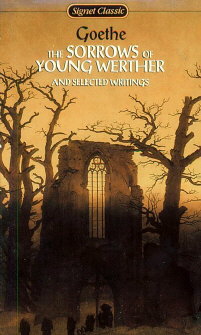

Like the period it ushered in, and like the party where Werther becomes smitten with Lotte, The Sorrows of Young Werther is filled with sturm und drang: "storm and stress."

It's a perfect book of adolescent emotions, and the book was the product of the sort of love lost, hopelessness, melodrama that sends many teens into bouts of depression knowing that they alone have experienced the tragedy of love lost so very deeply.

Goethe, 25 at the time, was on the rebound from an emotional break-up, and he penned the novel in an amazing burst of energy in just a few weeks; it was his catharsis--his means of purging himself of all the violent emotions attendant to a failed love. Unfortunately, the book also became a cult favorite; the cult of Werther saw young men all over Europe wearing blue frock coats with yellow vests and stockings and, in some cases, committing suicide like the title character. This disturbed Goethe who insisted they were missing the point. Werther is a disturbed individual. His emotional responses are genuine to a point, but he lets his emotions unbalance him, to completely unseat his reason. Werther, like Goethe, needed to write a book, to get over it.

Nevertheless, for many Werther was the epitome of the Romantic sensibility, of being keenly attuned to emotion, any emotion, as a means of transcending "normal" reality.

Another writer, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, echoed this emotional response in Book III of his Confessions (which is in our textbook):

I only felt the full strength of my attachment when I no longer saw her. When I saw her, I was only content; but, during her absence, my restlessness became painful. The need of living with her caused me outbreaks of tenderness which often ended in tears.... If ever the dream of a man awake resembled a prophetic vision, it was assuredly that dream of mine. I was only deceived in the imaginary duration; for the days, the years, and our whole life were spent in serene and undisturbed tranquillity, whereas in reality it lasted only for a moment. Alas! my most lasting happiness belongs to a dream, the fulfillment of which was almost immediately followed by the awakening... (1634)

Like Rousseau, Werther immerses himself in nature and gives himself over to his deepest emotions to try and throw off the limiting, dull trappings of society. Order and reason are for the half-dead; true happiness, they felt, was giving into weeping and love, emotion and passion.

This notion was influenced, in part, by the writings of Immanuel Kant. Following Berkeley, Locke, and the other empiricists and anti-rationalists, Kant sensed that people can't know everything. He separated the physical from the metaphysical, science from philosophy, the phenomenal (world of physical phenomena) from the noumenal (the world of forms, higher reality). In his Critique of Pure Reason he suggests that man is cut off from noumenal (the world beyond physical phenomena) reality. The rational approach works with the surface world (space, time) but not with other (inner? spiritual?) knowledge. This presented a problem: how does one deal with moral questions if morality (and other abstract knowledge) cannot be known with scientific certainty? Kant suggested that people can get glimmerings of the noumenal through struggle with ethical situations, through feelings. Note: an excerpt discussing Kant's "Antinomies of Reason" is in our course Supplamental Readings).

Werther is the outsider, youth thumbing its nose at science and The Establishment while embracing feelings and relishing interior struggle. Look at the various pronouncements that Werther makes about society and convention; a particularly pointed speech is Werther's scathing attack on the idea of a "husband" which he delivers to Charlotte:

And what do they mean by saying Albert is your husband? He may be so for this world; and in this world it is a sin to love you, to wish to tear you from his embrace. Yes, it is a crime; and I suffer the punishment, but I have enjoyed the full delight of my sin. I have inhaled a balm that has revived my soul. From this hour you are mine; yes, Charlotte, you are mine! I go before you. I go to my Father and to your Father. I will pour out my sorrows before him, and he will give me comfort till you arrive. Then will I fly to meet you. I will claim you, and remain in your eternal embrace, in the presence of the Almighty. (124)

Through emotion and the forces of nature Werther attempts to transcend the ordinary world. Note how often he talks about being "absorbed" (by Lotte's presence, by love, by trees and birds and other elements of nature). He often associates this absorption with achieving godhead, and he confuses himself first with an ascetic, then a saint, eventually Christ.

November 15Thank you, Wilhelm, for your cordial sympathy, for your excellent advice; and I implore you to be quiet. Leave me to my sufferings. In spite of my wretchedness, I have still strength enough for endurance.... What is the destiny of man, but to fill up the measure of his sufferings, and to drink his allotted cup of bitterness? And if that same cup proved bitter to the God of heaven, under a human form, why should I affect a foolish pride, and call it sweet? Why should I be ashamed of shrinking at that fearful moment when my whole being will tremble between existence and annihilation; when a remembrance of the past, like a flash of lightning, will illuminate the dark gulf of futurity; when everything shall dissolve around me, and the whole world vanish away? Is not this the voice of a creature oppressed beyond all resource, self-deficient, about to plunge into inevitable destruction, and groaning deeply at its inadequate strength: "My God! my God! why hast thou forsaken me?" And should I feel ashamed to utter the same expression? Should I not shudder at a prospect which had its fears even for him who folds up the heavens like a garment? (96)

Even as he says he's got "strength enough for endurance," he is contemplating (not for the first time in the book) his suicide. He confuses his self-destruction with the sufferings of Christ. In his own mind he is special, as his name Werther ("worthy") suggests.

This produced a major milestone in the nature of the literary tragic hero. Werther's conflict is not directly with society or a king or Fate or God or nature or supernatural forces; the tragedy arises out of the character's own personality; making this the first truly noteworthy psychological novel.

As an epistilatory (series of letters) novel, The Sorrows of Young Werther is not unique; this was an invention of the latter half of the 18th century, but it did not originate with this book. Still, Goethe uses the form to full, logical effect. As a series of letters the story is more intimate; it's a perfect form to reveal the different characters' mental states (most of the reality is filtered through Werther's mind); it limits the point-of-view to show Werther's feelings, biases, shortsightedness. As Werther changes through the course of the story it affects his style, which is often fragmentary, filled with exclamations and even ramblings.

And the use of the editor to complete the story is another great touch. The editor provides distance, allows us to see Werther in a conventional light rather than through his own eyes. The editor is sympathetic but not confused. His straightforward, even aloof, style lends credibility to the work, making it as-if-real, and the matter-of-fact exposition at the end of Book Two puts the death in perspective: this is not a larger-than-life tragedy; it's a sad, needless death of a confused young man who has forced himself into an impossible situation.

(Note: next week's lecture will discuss several elements of Romanticism--all of which can be applied to The Sorrows of Young Werther. If you are writing about Romantic elements in the novel, you may want to look ahead)

![[schedule]](button12.gif)

![[discussion questions]](button44.gif)

![[writing assignments]](button41.gif)

![[readings]](button13.gif)