don't confuse Romanticism with love

World Literature generally avoids looking at English and American Literature (not because these places are from another world but because there are separate survey courses which cover them). Still, before looking more closely at the French and German poetry in our textbook, a quick discussion of some well-known English poems from the Romantic era will illustrate the characteristics, subjects, issues most common to Romanticism. (Note: these poems are available on the Readings page for this course).

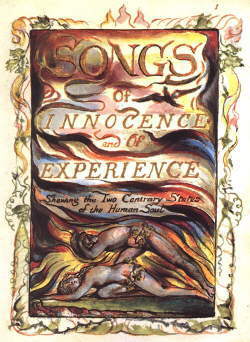

The scathing attack of unfeeling social institutions is unmistakable in"The Chimney Sweep" by William Blake. Europe was blighted with venereal disease, unwanted children, child labor, hunger, a wildly-inequitable distribution of wealth. The institutions that were designed to deal with these problems were meagre, often cruel. Dickens' Oliver Twist and Hans Christian Andersen's "The Little Match Girl" offer two more glimpses of how innocent children were exploited and abused. This inhumane (and inhuman) treatment of innocence was the subject of several Romantic poems, several by William Blake. In "The Chimney Sweep" the best that these orphaned children, forced to work in the coffin-like confines of sooty chimneys, have to hope for is death. Like the later American Romantics (the hippies and the yippies of the 1960's and 70's), the earlier Romantic movement embraced political and social protest.

As outsiders many of these poets turned to nature rather than man-made systems to find true meaning. In "The World is too Much with us" by William Wordsworth, the speaker wishes he'd been born a primitive, not in the center of English society. As part of the Establishment the narrator moans: "We have given our hearts away, a sordid boon!" He longs for the restorative powers of nature where mythic truths, "sight of Proteus rising from the sea; / Or hear old Triton blow his wreathèd horn," would fill his life with joy and meaning.

Transcending the mundane world and finding true meaning in nature is also projected in John Keats' "When I have Fears". The speaker, beset with the very human fears of mortality and the insignificance of existence eventually loses his sense of self in the awesome power of "the night's starred face." In the end the self falls away; the speaker's consciousness is absorbed into the pantheism of the cosmos.

Lord Byron was a quintessential outsider. Rich and aristocratic, he was a wild adventurer who took up causes as his fancy struck him. His poem "She Walks in Beauty" shows how the Romantics looked to non-conformist images of beauty. Here the typical golden-haired innocent is replaced with a dark, gothic lover. Not content to paint her in conventional light images, Byron writes,

And all that's best of dark and bright

Meet in her aspect and her eyes:

Thus mellowed to that tender light

Which heaven to gaudy day denies.

This raven-haired beauty has elements of both dark and light. There are mystery and danger blended with purity and innocence in her aspect; the stereotype of "light and day" does not equal "good" here; instead, it's "gaudy" and unreal.

"Kubla Khan", by Samual Taylor Coleridge, can be seen as an early example of psychedelic poetry. The imagery is lush, evocative, exotic. And most sources agree that the poem was not merely the product of a natural dream; the dream was most-likely opium induced. In any case, exotic dream and drug imagery was not uncommon in Romantic poetry, where the interior vision was seen as more genuine than the forced dull motions of everyday reality. "Kubla Khan" extends the darkness of Byron's "She Walks in Beauty." The journey is to the underworld where the final image what must be the fallen Lucifer

Weave a circle round him thrice,

And close your eyes with holy dread,

For he on honey-dew hath fed,

And drunk the milk of Paradise

mixes dread with fascination.

To summarize, Romantic literature, though anti-Establishment, had its own conventions; among the most basic ideas were

institutional behavior was limiting, not to be trusted

society and the aristocracy were corrupt and unfeeling, unconcerned with serious social problems that needed to be addressed

the primitive and rustic provided freedom that civilization quashed

nature provided a truer source for genuine knowledge

emotions, not reason, were the key to transcendence

the melodramatic and the gothic presented emotional moments that led to insight

the outsider and the adventurer were role models

A quick review of Goethe's The Sorrows of Young Werther will reveal all of these elements.

Heinrich Heine

If Heine's poems seem overly simple with their common language and their te-dum-te-dum-te-dum rhythm and meter, the simplicity is a bit deceptive. He's not difficult to understand, but there is often some tension, some subtler irony in his works.

The first poem in the text, "The Rose, the Lily, the Sun, and the Dove," really is a good starting point:

The rose, the lily, the sun, and the dove,

I loved them all once in the rapture of love.

I love them no more, for my sole delight

Is a maiden so slight, so bright and so white,

Who, being herself the source of love,

Is rose and lily and sun and dove. (1756

Now how sweet is that? Drippingly sentimental, this verse could easily grace a Hallmark Valentine's Day card. The narrator is so entranced with his lovely young woman that she has become the world for him. This conventional turn seems straightforward enough until one looks again at the first three lines. Even if we ignore the value that the Romantics place on nature, the forces of nature he lists are all conventionally positive, beautiful, nurturing; viewed as symbols they can represent elemental states (love, death or purity, enlightenment, spiritual transcendence). The point is not really how deeply we choose to interpret these images; in any form they are positives; this is reinforced in the end of the poem when they are equated to the love the narrator now feels for this maiden. The real irony in the poem is that these forces all had the power to move the speaker to love until he met this maiden. Now they are dead to him: "I love them no more." The urge to love the maiden has blinded him to the wider world.

Compare this and the next few poems to The Sorrows of Young Werther where love of a woman (or being in love with the idea of love) blinds and binds, unbalances the main character.

This point is explicitly stated in "My Beauty, My Love, You Have Bound Me." The binding is sensual and sensuous--the speaker is captured in both heart and mind, and he asserts that he's happy to be so caught in love's arms. But note the final phrase: "The happiest Laocoon" (1757). If you're unfamiliar with the myth, take a look at the footnote in our text. Heine could have chosen another allusion (yes, he'd have to work with the rhyme, but he certainly could have managed). Why does he select a myth that shows a man in a life-and-death struggle? It certainly adds a tinge of menace to the poem.

Both "A Spruce Is Standing Lonely" and "A Young Man Loves a Maiden" show love as a pitiable state, often unattainable, often unfair. The first poem is filled with impossible longing. Ironically, even if the spruce were to travel to his desert love, or if the lonely palm could make her way to the "ice and snowflakes" (1756), they would not thrive; they would perish out of their elements. It's reminiscent of the classic German film The Blue Angel (on my recommended list!). And the second poem shows that meanness, the unfairness, the hurt that can surround love.

Heine's socio-political poems are protest poems calling for change and action. "The Silesian Weavers" was occasioned by an actual protest of unacceptable working conditions. Heine uses the image of weaving very artfully as the workers weave a shroud of death and a tapestry of "threefold doom" (1758) (much as Madame de Farge in Dickens' A Tale of Two Cities knits the roll call of death by the side of the guillotine.

By contrast "The Migratory Rats" seems equally afraid of both the rich and the poor, comparing both to rats. Of course the fat rats (the rich) hoard all of the food which prompts the hungry rats to march, but when the Establishment presents its empty promises and the hungry rats revolt, Heine doesn't show admiration for the mindless pack. Nevertheless, his poem calls for a change in the conditions that allow either sort of rat to exist.

And then there's "Morphine." The desire to reach altered states of consciousness led many in the Romantic era to take drugs; opiates were particularly popular at the time. In Heine's poem morphine is not really a vehicle for transcendence; it's a means of escape. The speaker is seeking "a kind reprieve" (1763) from whatever pains him in the world. Again, Werther comes to mind by the poem's end when the narrator seeks morphine's "paler brother": "Oh, sleep is good, death better--to be sure, / The best of all were not to have been born" (1763). The sturm und drang of the world is too much for this speaker. Perhaps like Werther he is obssessed by an impossible love; maybe the inhumanity in the world has overwhelmed him. He uses the drug as a temporary release, but he's clearly contemplating suicide. Life steeped in emotion may be life genuinely felt, but in the end he wishes he'd never had to endure it.

Victor Hugo

Yes, this is the Les Mis and Hunchback of Notre Dame author. But read the headnotes in our text; he was very prolific in several genres; he was quite well known for his poetry.

"Memory of the Night of the Fourth" is a powerful protest piece. It needs little explanation, but I'd urge you to look at the careful use of graphic detail and suggestive imagery, the loaded situation of depicting innocent children killed by stray bullets and the bitter sarcasm of the second half of the poem.

The other poems in the text show the unique way the author/poet perceives the world and acts as prophet to let the reader see things in fresh ways.

It's a pity that "Et nox facta est" was never completed because, arguably, it would have rivaled if not dwarfed Milton's epic Paradise Lost.

Not exactly the Rolling Stones' "Sympathy for the Devil," the poem, nonetheless, tries to imagine the agony of Lucifer's fall while not sugar-coating the devil's crimes against heaven. This tension is achieved throughout the poem as the demon sinks further and further into darkness, as light narrows to a point and then vanishes altogether.

Much of the language humanizes the fallen angel and does evoke sympathy: Lucifer feels "aghast," "alone," "dumbfounded," "grim," "sad" as "the horror of the chasm imprinted on his livid face" (1802). And in section III there is the pain of his transformation:

In an instant he felt some horrendous growth of wings;

He felt himself become a monster, and that the angel in him

Was dying, and the rebel then knew regret.

He let his shoulder, so bright before,

Quiver in the hideous cold of membraned wing, (1803)

But Hugo is not overly-sentimental. Lucifer is also described as "sinister and pulled by the weight of his crime" (1802); he is a "bandit" who committed a horrible "affront" with his own "guilty hands."

Here the poet tries to translate the mythic, higher knowledge, into some form that can be understood by all of us. The poet is the visionary and the prophet, transcendent and illuminating. The excerpt of the poem in our text concludes:

Who could fathom you, oh chasms, oh unknown time.

The thinker barefoot like the poor,

Through respect for the one unseen, the sage,

Digs in the depths of origin and age,

Fathoms and seeks beyond the colossi, further

Than the facts witnessed by the present sky,

Reaches with pale visage suspected things,

And finds, lifting the darkness of years

And the layers of days, worlds, voids,

Gigantic centuries dead beneath giants of centuries.

And thus the wise man dreams in the deep of the night

His face illumined by glints of the abyss. (1808)

Of course this could apply to the archeologist, the cultural anthropologist, the psychologist and the philosopher. For the Romantics, the "wise man dream[ing] in the deep of night" was also, most certainly, the artist / poet.

![[schedule]](button12.gif)

![[discussion questions]](button44.gif)

![[writing assignments]](button41.gif)

![[readings]](button13.gif)