modernism?

Last week's lecture and readings briefly introduced you to the rapid changes and diverse approaches that occurred with the coming of the 20th century. Some are based on game theory, some embrace the surrealist movement; some are responses to equally-rapid changes in other fields (psychology, sociology, political theory, even mathematics and physics). There are really many different movements in the 20th century, but often these different experiments in literature (and the arts in general) are collectively referred to as "modernism."

the play within the play (without the play)

An old man's wife dies. Soon after this his son marries and has his new wife come live in the family home. The father no longer needs the master bedroom with the big bed and moves into a smaller room away from the center of the house. The son has replaced the father as family man and head of the household, and the father is now treated like a son. After awhile the father relishes his new lack of responsibility, his freedom; he has grieved for his dead wife long enough, and he grabs on to a second chance at life by once again seeing the simple pleasures of the world through child-like eyes. Wandering to a park he enjoys the simple touch of grass, the sun and sky, the children playing. He is shaken from his light moment when a girl accuses him of being a lecherous old man trying to look up her dress. He retreats to his small room with nothing left to him but staring at the blank wall--his future.

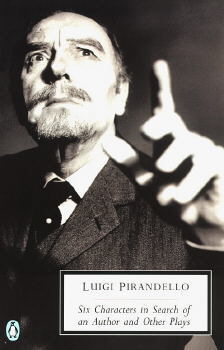

This bare plot summary of Luigi Pirandello's "The Soft Touch of Grass" illustrates one of the author's key themes--reality is relative, based in large part on point of view. The little girl was not and could not be inside the old man's head. Her assumption that he was spying up her dress was probably based on past experience or parental warnings. She wasn't lying, but she was not telling the truth; she was not aware of the old man's truth.

This theme is present in much of Pirandello's work and is perhaps most succinctly expressed in the title of his play Right You Are--If You Think So. It's certainly a central theme in his most famous play, Six Characters in Search of an Author, where we are asked to separate reality from illusion, truth from fiction.

Influenced by French philosopher Henri Bergson, Pirandello was a skeptic. But he wasn't just a product of the lack of solidity in the 20th century; he had personal reasons for his sense that truth could never be fully communicated or known. Max Halperen points out he had

...a reason that made this concept that men cannot possibly understand one another become an obsession with him. He was for many years tied to an insane wife who gave him no rest. Among other things, her insanity took the form of a violent, raging jealousy. Pirandello did everything he could to reassure his wife; he wouldn't go out, he turned from his friends, he even yielded up his entire salary to her. But his wife's image of him remained the same, so that alongside his own picture of himself as a patient, resigned, pitying family man, there alway hovered the image in his wife's mind of a loathsome being who gave her nothing but pain. As far as Pirandello was concerned, such conflicting images underlay even the most normal of human relations, though in insanity the problem is multiplied, or at least seen more clearly.

Compare this to the Father's speech about his sense of self contrasted with what the other characters think of him. Of course, our hearing him say that does not mean that he really feels all that blameless in turning The Mother away or in nearly sleeping with The Stepdaughter. He could very well be saying it to make himself look good. We can never know the truth of his perception because we don't have his perception.

A related theme in the play is the truth of art, writing, all forms of communication. Just how much truth can there be in a work that is artificial, shaped, invented? This is not, after all, history; it's fiction. The characters want to bring the play closer to the author's truth by acting the parts themselves, but that is much like having a dance without dancers--interpretation of a form is how art communicates, and The Manager points out, "Acting is our business here. Truth up to a certain point, but no further" (2188-9).

Even so-called "reality-based" television shows are edited. Days of footage are compressed into 50-minute shows; the selection of images squeezes out the boring bits to dramatically heighten the action and to create a sense of story. The stories are often misleading (artificially crafted to create something viewers want to watch). But just as art is not the same as history, historical truth is also selective and may fail to communicate much that is substantial. Watching a truly vacant lot for twenty-four hours may be real, but it is neither entertaining nor very illuminating. It deadens rather than communicates. So fiction may have a couple of advantages over history in revealing truth (not just factual tidbits but ideas about the human condition): 1) if it's entertaining, people may attend to it (without watching or reading or hearing there won't be any communication); 2) it doesn't pretend to be really real; it stands for kinds of behavior and incidents and actions that we recognize as like life.

Then again, that may all be imagined. Art may only appear to be like life because our perceptions and understanding of life are limited by the focus of the lens through which we view the world.

?

![[schedule]](button12.gif)

![[discussion questions]](button44.gif)

![[writing assignments]](button41.gif)

![[readings]](button13.gif)